Curator of The National 2019: New Australian Art at Carriageworks, Daniel Mudie Cunningham, shares his thoughts and inspirations behind his curatorial vision for the project.

*

What I prefer, about postcards, is that one does not know what is in front or what is in back, here or there, near or far, the Plato or the Socrates, recto or verso. Nor what is the most important, the picture or the text, and in the text, the message or that caption, or the address.[1]

*

Australia’s largest tourist attraction during the bicentennial ‘celebrations’ of European colonial settlement was World Expo ’88 in Brisbane. It opened to the public on 30 April 1988, a week after Billy Ocean’s Get Outta My Dreams, Get Into My Car bumped Kylie Minogue’s I Should Be So Lucky from the top spot on the Australian Top 40. It is probable that Kylie’s song was a staple on the AM radio airwaves as you crossed the Expo threshold through the colossal AUSTRALIA sign Ken Done designed for the entrance. Given Australia’s reputation as The Lucky Country, thanks to Donald Horne’s famous 1964 book, Kylie’s hit may as well have been the unofficial postmodern national anthem as bicentennial fever shook postcolonial Australia.

Is there an Australian art equivalent of a chart-topping song? No, so let’s settle on whatever was on the cover of Art & Australia as Expo ‘88 opened. The autumn 1988 edition of the perennial journal reproduced on its cover Eugene von Guérard’s Mt William from Mt Dryden, Victoria (1857). The words “Australia 1788-1988” appeared in small print adjacent to the masthead. Among its pages (predominately surveying white male artists with zero Indigenous representation) was artist Brian Blanchflower’s personal response to von Guérard’s anachronistic colonial landscape.

Eugene von Guérard (1811-1901) died a couple of years after the decade-and-a-half it took to build the Eveleigh Railway Workshops, now known as Carriageworks. What does von Guérard and Carriageworks have in common? Nothing unless you consider how their respective bonds to unspoiled nature and the architectural residue of an industrial past are frequently described as ‘sublime’ and ‘picturesque’. Coincidentally, von Guérard’s cover appearance on Art & Australia’s bicentennial issue occurred at exactly the same time that the Eveleigh Railway Workshops ceased with steam powered industry in 1988.

A month before The National 2019 opened, I turned 44 years of age. Back at the scene of my birth in February 1975, the number one song on the Australian Top 40 was Please Mr. Postman by the Carpenters. “I remember it used to play when I was in the hospital,” commented my mother when I posted the music video on Facebook the day I started writing this essay. In the clip, infantilised adult siblings Karen and Richard Carpenter spend a sunny day frolicking in Disneyland with Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Goofy. Music clip meets tourism travelogue, the three-minute song is a postcard from mid-1970s upper-middle-class-late-capitalist-white-heteronormativity (a stark contrast from the track’s Motown origins).[2]

I haven’t sent a postcard in a long time, but I frequently post found visual matter on social media. In my view, this gesture is one and the same—a kind of fleeting, fragmented and non-linear pop-cultural tourism for the algorithmic feed of our time(line)s. Characterised by brevity and inexpense, a printed postcard does a similar thing in that it reduces our experience of consumption down to its very basics, a snapshot of the here and now summed up by a swift sentence or three:

Thinking of you! Having a great time! Wish you were here!

Despite a tension between its mass reproduction and subsequent personalisation, the intimacy of the postcard and other souvenirs of travel become a mnemonic device to remember otherwise fleeting experiences. Of the impulse to document tourism and travel, urban planning theorist Linda C Samuels writes: “To gaze upon the uncommon or the extraordinary and to institutionalize this gaze by capturing and saving it, converts the temporariness of the trip into the permanent memory palaces of souvenirs, photographs and books.”[3] This permanency shifts meaning over time as these artefacts circulate in the secondary market hereafter where images are abandoned, awaiting new adaptive uses. Tony Albert’s orphaned (stolen) relics of ‘Aboriginalia’ for instance, are kitsch mid-century depictions of First Nations people which he collects and reclaims as politicised nostalgia, a house of cards set to topple at any moment.

The logic and expectation for The National is evoked in its title. Artists are selected from across ‘the nation’ to form a sample of contemporary practice represented by a small group of living artists fortunate enough to be selected from a larger national pond (artists competing at ‘the nationals’ if we applied a competitive sport metaphor). Time and again, I contemplated the idea and form of the postcard as I was meeting artists in their studios across the country. Images encountered on my travels became postcards of a time and place that I imagined mailing to a future version of myself. Receiving a postcard is joyous digression that punctures the otherwise humdrum routine and schedule of daily life. When Sean Rafferty mailed me a postcard from Port Douglas in the tropical far north of Queensland during a field trip where he met farmers and collected their fruit cartons and stories, it dawned on me that his Cartonography project is itself a friendly postcard from the regions: sunshine for dark times.

Employing the postcard as a metaphor of memory and digression, what has been delivered at Carriageworks for The National 2019, navigates the present moment, through the past, for the future. The exhibition maps memory and place-making, where the work of art is an unsealed letter teeming with postmarked messages for an unspecified reader—the emotional tourists among us who feast on another’s experience to quench an otherwise aching emptiness. A fundamentally public message, a postcard assumes an intended reader, and speaks to this person as if they are the only possible recipient. The addressed stress on destination circumvents unplanned interceptions en route—new meanings from new audiences—dotted along the way. Exploring the slippery edges of truth and fiction, the artists presented at Carriageworks reflect on the individual’s place in a precarious and ever-shifting world, sending their work into the world like postcards mailed from the visual wreckage of local, national or global contexts.

Following the 30 year anniversary of World Expo ’88, Ken Done’s AUSTRALIA is updated by Sam Cranstoun’s UTOPIA. Publicly situated outside Carriageworks at the exhibition entrance, the word UTOPIA reads like a warm welcome, promising optimism through its sunny Done inspired letterforms and thinly disguising the dark dystopic flipside to come. Roland Barthes writes, “the mark of utopia is the everyday; or even: everything everyday is utopian”.[4] Much earlier in the twentieth century during the industrial heyday of the Eveleigh Railway Workshops, an everyday sight would have been locomotive steam. Tom Múller responds directly to this history with Ghost Line, a site-specific installation using fog as sculptural matter that animates the Carriageworks precinct with a spectral trace of its past use. Thom Roberts similarly engages with the rail culture of the site through his personified train portraits installed as banners within the massive signage structure at the Wilson Street entrance to Carriageworks.

Stepping inside the building, the foyer of Bay 21 presents two video installations reframing Hollywood cinema from the late twentieth century. Nat Thomas recreates a short scene from a feature film while Tara Marynowsky uses film trailers as a canvas for hand-drawn animations. Positioned at the internal entrance of the exhibition, Thomas’s Postcards from the Edge invites audiences to lay on a platform to simulate a scene from the 1990 film of the same name. You too can be Meryl Streep’s approximation of Carrie Fisher hanging for grim death from a tall building. For Thomas, fear can be an illusion, a carefully staged and hashtagged photo-opp for social media. Our catastrophised lives are often better off than we realise—especially if it means risking life for a viral and fame-making picture.

In contrast, Marynowsky’s Coming Attractions ‘defaces’ the female protagonists in film trailers for Pretty Woman (1990), Indecent Proposal (1993), Species (1995), and Shakespeare in Love (1998) by violently scratching into the surface of each frame of celluloid to create a humorous feminist response to the snowballing backdrop of the Harvey Weinstein takedown.

Long before social media, music videos were a key access point to how stardom could be engineered through image and persona. In the video installation Oh Yeah Tonight, Melanie Jame Wolf takes aim at these three most repeated words in pop music: oh, yeah, tonight. Packed into three-minute pop songs are either complex mantras or complete reductions of how sexuality and power come to shape an understanding of the world, particularly one formed in youth. Reared in the eighties MTV era, Wolf creates seductively queer-feminist deconstructions of image and text to dramaturgical effect.

Text is central to Troy-Anthony Baylis’s ongoing series Postcard. Baylis repurposes metallic Glomesh handbags and purses from second-hand stores into works that spell out place names, while visually referencing Aboriginal breastplates. Offering armour through a set of cultural conditions specific to his Papua New Guinea lineage, Eric Bridgeman’s shields meld traditional designs of his homeland with a visual language drawn from sport and art. Bridgeman’s shields are a communal enterprise with family and friends, a private language between kin transformed as contemporary abstraction when it meets the white gallery wall. The process of making for Baylis, in contrast, is an intense and laborious stitching of camp fabric into an implied correspondence between the drag queens and ‘sistagirls’ either named after or residing at the locations to which they speak.

Drag has long been central to the work of Luke Roberts. 2019 marks the fortieth anniversary of his most enduring performance persona, Her Divine Holiness Pope Alice, who first appeared at Swish Ball, a party held in suburban Brisbane in 1979. Roberts marks Pope Alice’s birthday with a performance spread across Carriageworks and the Art Gallery of NSW on the opening weekend of The National 2019. In the exhibition, Roberts presents a new photographic work Mars Rusting, which reimagines and contemporises baroque painter Diego Velazquez´s Mars (c.1638).

Whether high or low, personal or political, old or new, the process of mining diverse visual archives is a common denominator. Sensitive to the ontological relationship of photography to death, Cherine Fahd privately mourns a grandfather she never knew through a form of public empathy by responding to family photos that document his funeral at Rookwood Cemetery in 1975. Julie Fragar’s speculative and symbolic self-portrait imagines the unknown future event of her death in paint, to potentially decouple fear and mortality. For Clare Peake, it is a reverence for dead objects, the failed attempts at making in the studio become a shamanic coat of many colours.

As the exhibition advances further back of Bay 21, the archive breaks down and compacts into the landscape. Amala Groom navigates a forest of gum trees near her home on Wiradjuri land through a video performance that unites marriage ritual and spiritual rite as a decolonising gesture. The Crocker Land Expedition is Mish Meijers and Tricky Walsh’s recreation of the 1913 voyage of the same name, which involved a search for land in the Arctic Circle that turned out to be a mirage. Populated by an army of disembodied limbs, Meijers and Walsh recreate an isolated desert island, scattered with remnants of disaster. In the space directly adjacent, a Tower of Babel comprised of household domestic objects and whitegoods is assembled and destroyed by Eugenia Raskopoulos. Opposite her video projection is a suspended red neon sculpture that swings back and forth like a pendulum of doom, an edict of (dis)order.

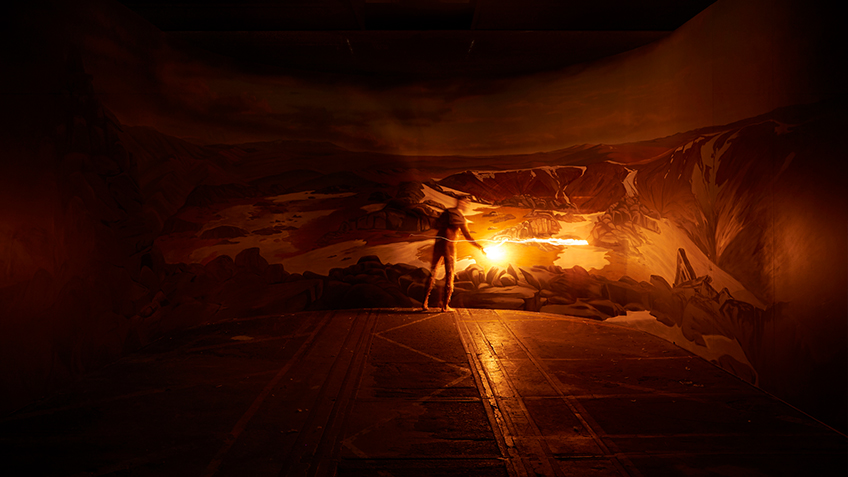

Concluding this trip like a strange revisioning of Plato’s Cave, Mark Shorter endorses the proposition that Eugene Von Guérard and Carriageworks have something in common, strange bedfellows they may be. Panoramic and romantic, von Guérard interpreted the Australian terrain as peculiar and otherworldly, capturing antipodean space firmly within a European lens. Adopting an outlandish performance alter-ego called Schleimgurgeln—a self-professed time travelling landscape painting critic, naked and feathered with boiled eggs for eyes—Song for Von Guérard employs absurd tactics to rethink the Vienna-born artist’s canonised work. On occasions, Shorter activates the space through performance, enlightening the landscape with a struck match.

Exit through the giftshop and get a postcard from dystopia.

Visit The National 2019 at Carriageworks.