How do I survive? I hustle. Everything is a hustle. Creating contacts, getting people to hire you … Do I worry? Do I feel insecure?

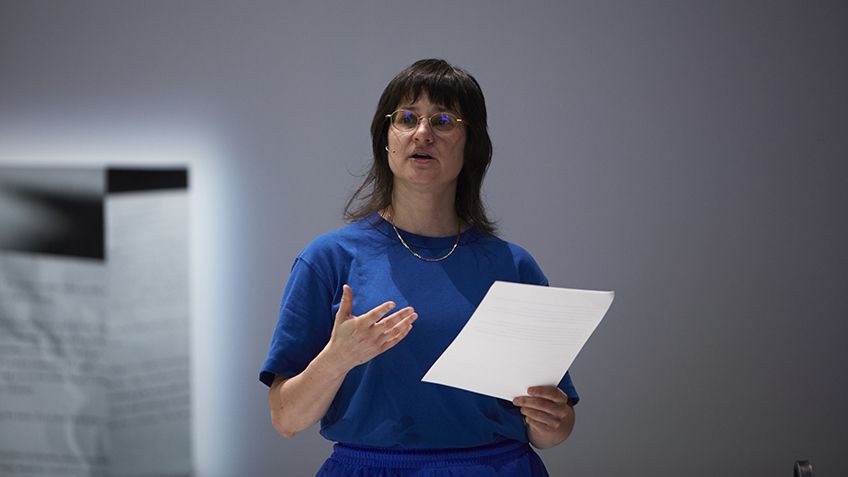

The last performance I saw before the 2021 lockdown was Sarah Rodigari’s On Time, on the closing day of the The National 2021: New Australian Art at Carriageworks, curated by Abigail Moncrieff. Dressed in her “gym clothes” – matching ultramarine shorts and t-shirt, short white socks and flat brown shoes, Rodigari delivered a monologue collaged from 12 hour-long interviews with staff from Carriageworks. The result was a riff on the notion of casual – labour, clothing, relationships, sex.

On a platform about three metres square, were 12 steel stands, kinked at the top, with barley sugar twists in their stems. They were placed in a seemingly random arrangement, with two lying down. I had seen this as a trace installation when visiting the exhibition a few weeks earlier after Rodigari had performed the first iteration of On Time during the opening weekend of The National. On the wall adjacent were giant photographs of pages of text crumpled then spread out again.

… she never seems to have the time or the money… . The more time she has, the less efficient she is.

More subtle meanings came to me later: the twists in the stands were of varying lengths, containing one to twelve bands representing the cycles of a day. Forged by Eveleigh Works, one of the last remaining industrial workshops in Australia, these markers of time connected On Time to Carriageworks’ long tradition of industry and manual labour. They were moved around the stage by the artist as she recited, pointing towards and away from the audience, recumbent, turning; sometimes they were mere props she leant on with one hand, holding her sheaf of papers with the other.

There is theatre in Rodigari’s deadpan delivery. Her accent becomes more English. The careful placement of hand in pocket, the shorts worn Harry Highpants style. You wouldn’t want to run into your boss, or ex, in casual clothing. She is crisp, laconic, wistful, wry. She corrects her pronunciation – or offers alternatives. It’s associated with stätus – stātus – stätus.

There is philosophy, politics, ambivalence; the various contexts overlap to the universal. There’s no pressure, you don’t lose your independence. … There’s a stigma. It’s assumed to be a stepping-stone to a more serious relationship, it makes you really think about the function of casual in society. … There’s no such thing as casual after the age of 30.

There is yearning, mourning, pathos. There’s no communication, you’re just left there, alone. … It felt pretty bad. … There’s an assumption that because it’s casual, it doesn’t affect you but it does.

It’s a sliding scale, she says, looking up at the audience, People say, yYou’re casual. Just. Casual.

I felt myself unexpectedly moved. I thought of all the people who had lost work during the closure of Carriageworks in 2020 with the first wave of COVID-19. I thought of the casual relationship I had ended the night before, with relief, yet also considerable pain. Of the thwarted aspirations, the aesthetic and social judgements, the constant uncertainties facing artists, casual teachers, hospitality and front-of-house workers, of the precariat who in this nation alone number millions. I thought of the whole grotesque spectrum of inequality.

Four days later, lockdown began. And On Time seemed more apposite, more elegiac than ever.

I catch up with Sarah several weeks later in the late afternoon. She is pleased with On Time. She claims not to get post-performance come down and, in any case, had been focussed on the next gig, a performance with Vitalstatistix Theatre in Adelaide the next week (she made it across the border just in time).

We walk around Rushcutters Bay Park through the lockdown throng, beneath clouds of screaming cockatoos bedding down for the night. Masks are not yet mandatory. We talk about politics, labour, surviving as an artist, models for greater equity. Rodigari relies on teaching. Not untypically, her performance installation for The National cost three times as much as the artist fee. The balance was made up with a grant from Create NSW.

‘I think artists should get money to create works,’ Rodigari says. ‘And arts organisations should get money to put on works. So, there’s not this idea of … this very cryptic government agenda where there are less and less small to medium arts organisations, less independent artists and small companies, so the only people able to get funding are in a particular tier making work for big venues, or supposedly significant exhibitions.

Rodigari continues, ‘What constitutes significant exhibitions? What makes artworks in The National any better or more deserving of funding than artworks for a show at an ARI? I think funding for the arts should go towards challenging culture and broadening our horizons, and major arts institutions like Carriageworks should be able to fund artists outright. That’s what I think!

‘I guess for me it’s about sustaining culture, so you go and see work regardless of … this idea of … elitism? It’s elitist!’

I remember Rodigari’s manipulation of the clock hands in On Time. Material change, measurement, direction, physical labour, evidence. Is it linear progression? Or just another cycle? What does progression mean anyway? Surely it is towards sustainability that we must progress, towards the maintenance of healthy cycles, away from the paradigm of linear exponential growth.

Rodigari talks of work she has been doing with queer accountants who are positing different ways of measuring value, for instance through dialogic data. ‘So, you can think about the Indigenisation of knowledge systems. The land is worth 1.5 million dollars, let’s say. But actually, we know it’s worth more than that because there’s a history, there’s a culture, there’s a whole First Nations relationship to that land that cannot be monetised. But valuing that requires a change in our mindset.’

I offer the view that addressing equity needs to come from within industries as well. ‘The heads of State galleries are paid $300,00 to $400,00K. While artists scrounge and work for free. Also, whenever we talk about funding crises, education and health top the list. But it isn’t just cuts to hospitals and universities that matter. It’s the fact that within those institutions, wage disparity is extreme. Vice Chancellors earn up to $600K, while us casual tutors can’t even get ten hours work a week. Professors – including art academics – and medical specialists in Australia, are paid a lot more here than overseas, including North America and affluent European countries. Until the top earners within our industries stand with us, there won’t be significant change.’

Rodigari discusses her position as a casual academic, how she doesn’t even consider herself as such, because she has a PhD. She prefers the term sessional academic.

‘How do I maintain morale among the students? How can I say the future is bright when in fact it’s bleak as hell? And in the real world, artists are often throwing daggers at each other to get the next opportunity. And I’m thinking if there was a universal wage, or income, would it be different? Can you strike without losing your job? Are the days of collective industrial action over?’

Written by Fiona Kelly McGregor