2006–07

I remember you. At a dive bar on a Thursday evening. It’s Soul Night; Curtis Mayfield is playing over the speakers. You’re at the bar with J, your girlfriend, who I’m crushing on from the dancefloor. You wave to H, our mutual friend, whose arms are pierced with impressive tats, and give me a casual glance. That’s the first time I saw you.

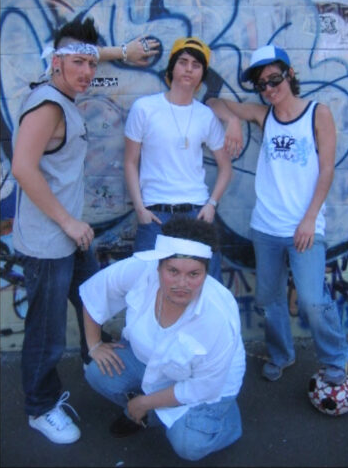

We became friends over countless nights at Cherry Bar, The Glasshouse, Queer and Alternative, and Aliyah, and exhibition openings at Gertrude Street, KINGS Artist-Run, Bus Projects, West Space, TCB art inc. and Seventh. One night, after eating curry on Flinders Street, we ended up at Drag Kings at Opium Den. The drag king scene was thriving in Naarm/Melbourne, where we grew up. You’d previously performed at Opium Den, including with your boy band, 4Evamore (your stage persona was Ricky, a loveable rascal whose passion for dance helped the band to unite and overcome womanising). That night, L was there—a woman in my ‘Cinema and the Carnivalesque’ tutorial, for whom I’d been making mix CDs in my head all semester. She was on a date. You followed me into a toilet cubicle, encouraging me to approach her. I casually told L that I was having a party on Christmas night. That was a lie. But we could easily organise an emergency house party, and we did.

The party, the bar, the opening—these are the spaces that mediated and structured our initial friendship. From the get-go, they gave us insights into how to shape the worlds we wanted for ourselves.

2003

You once told L, who became my partner, that you wanted to be an actor but soon realised you would only get bit parts as a petty criminal in Australian television and never be the star. I keep this in mind as I watch the video work Super Super (2003) in preparation for this essay. You appear in drag—at times, you are masked—as the villain, the victim, the superhero and the sidekick amid an intimidating metropolis. You have made yourself the protagonist by taking over the means of production, overseeing the set, costumes, camera, editing, everything. But even though you appear as the star of the work, your sense of self—as it manifests via self-portraiture, for example—is always relational.

2006

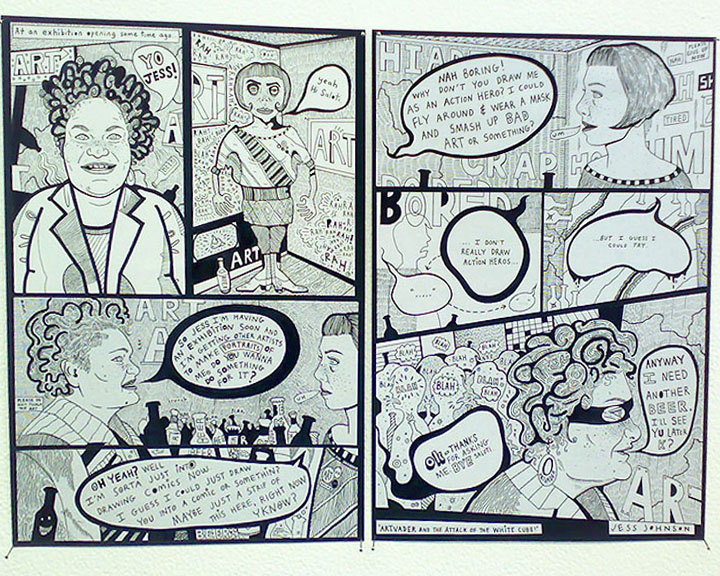

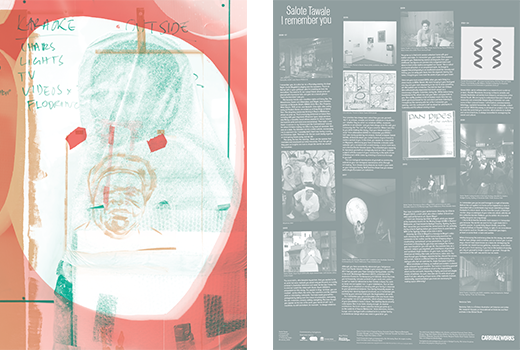

Your practice has always been about how you use yourself, the ‘I’, to critique, unmake and remake institutions of Australian art—whether they be artist-run initiatives (ARIs), museums, galleries or art schools—and you have always done this with your community, the ‘You’ and ‘Us’ of your practice. When I said this to you while drafting this essay, I had your whole practice in mind—from Affirmations (2002) to I remember you (2023)—but I was mainly guided by one project, Portrait of Salote Tawale (2006), at Seventh where you invited dozens of your friends to make a portrait of you. In the show, you appear as a pop artist on Myspace, referencing your love of karaoke; a blonde nudie calendar girl; a miniature doll; a butch dandy; a comic book hero; and a femme Pacific Islander queen. You unleashed your capacity to reproduce yourself non-biologically (and as a fluid, mutable subject) with the support of your community on the walls of one of Melbourne’s white cubes by directing a humorous homage to yourself.

The non-biological reproduction of yourself via community extends to your non-biological reproduction of kin through art-making. Your chosen family features as much in your work as your biological family. Both families shape how you appear within Anglo/European art institutions.

2017

Although you have consistently referenced your Indigenous Fijian and Pacific Islander lineage in your practice, it wasn’t until 2017 that you gave your Fijian biological family greater visibility in the work Burebasaga Marama’s (2017), presented at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA). Since this time, you’ve frequently included portraits of your aunts and uncles—as well as material references to their homes in Suva, Fiji, such as tarps and corrugated iron—in your installations. Your art has allowed you to establish an intimacy with your family in response to your geographical distance. Your family frequently appear as painterly free-standing plywood structures, as in I remember you, translating your personal history for the Anglosphere art world.

For I remember you, you constructed a life-size house made of corrugated iron at Carriageworks, which alludes to a memory of your grandfather’s home in Suva. The dwelling stands proudly in the space. But, if one looks closely enough, its shadow architecture: the brick-veneer suburban home you grew up in on the outskirts of Naarm/Melbourne—three bedrooms, kitchen, lounge, and a backyard with a clothesline for a nuclear family, a conventional design which was never a good fit for you.

2009

You grew up in that brick-veneer suburban home with your mother and sister. In I remember you, your sister Elisa appears alongside you. Referencing several photographs from your childhood, two figures are painted onto a plywood board and stand in front of the replica corrugated iron house —like a cutout at a tourist attraction or an amusement park. As though to suggest that photography is an insufficient vessel for memory and history, you cut away your faces from the plywood, leaving two holes. I imagine your mum took the photo of you and your sister.

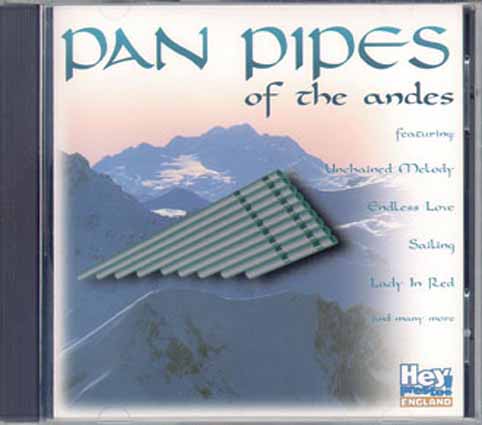

I first met your mum around 2009, when you were living in a share house on Miller Street. We were lounging in your front yard one day and your mum stopped by in her car to drop something off. We walked over to help her. You told her that I am Chilean. She enthusiastically responded that she’d served as a missionary in Bogotá, Colombia, during the 1970s before being transferred to Fiji, where she met your father and gave birth to you. She swiftly grabbed a CD of Andean music from her car, which you’d purchased for her and she’d just been listening to. I brought up this memory with her at the I remember you opening, and she continued to tell me about her adventures in Colombia and Fiji without missing a beat.

2013

Your mum is central to your performance Dressing Up (Ode to Mogul) (2013), a work which also cites a mother of American video and performance art, Susan Mogul.

I didn’t see Dressing Up (Ode to Mogul), which you staged at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Naarm/Melbourne, as I had moved to Gadigal Country, Sydney, by then. But I remember you recounted the performance for me, probably during a trip to Sydney before you moved there to undertake an MFA at the Sydney College of the Arts in 2016.

Dressing Up (Ode to Mogul) is a homage to Mogul’s video work Dressing Up (1973), which humorously examines her connection to her mother and the role that shopping plays in constructing ‘womanhood’ across generations. In your re-enactment of Dressing Up, you show and analyse the clothes your mum bought for you until age 30. You examine how, as a diasporic subject, you negotiate your inheritance of gendered and racialised Anglo traditions via your mum, but also Euro-American art history (the nude, performance, video, etc). You sieve through your heritages, examine the lies, discard the excess, and, in turn, insist on a different future for contemporary art in dialogue with, but not restricted to, Anglo/European traditions.

What constitutes art history, as method and content, is placed under pressure by your practice. You insist on inscribing yourself upon discourses and institutions of art in the Anglosphere, where we live and work, frequently in highly personal and playful modes of address. As such, how else am I to write about your work if not also adopting at least some of the methods (memoir, relationality, experimentation) you insist are necessary for making space differently?

2021–24

Since 2021, we’ve collaborated on a research and curatorial project, Parallel Structures, focusing on how to unmake and remake Australian art worlds from diasporic perspectives of the Global South. We are trying to understand how and if local art museums and universities (especially art schools) can undo some of their colonial biases—individualism, possessiveness, teleology, capitalist hierarchies, etc—in how to educate, collect and exhibit. While this essay is not about our project, I cite it here to make the point that your practice, which extends to multiple and varied directions, is always committed to reimagining the social and cultural.

2023

In I remember you you’ve paid homage to a night of karaoke. Behind the corrugated iron home at Carriageworks a room is decorated with a comfortable vinyl couch resembling vintage Fantastic Furniture stock. Across from the couch, a television monitor plays a catalogue of your video art, which, with the art film collective Garden Reflexxx, you’ve edited into a karaoke medley (anyone can sing along).

I like to think that the karaoke room appears in I remember you because ‘the worlds we want to live in get made first in nightlife spaces’, to quote Kelly Dezart-Smith, one of the curatorial fellows of Parallel. If Kelly is right, it’s no coincidence that projects such as Parallel and I remember you began, at least on some level, in bars and parties.

When discussing the preliminary ideas for this essay, we realised that we have always used ourselves and our distinct yet, in some ways, shared lived experiences as a basis for reimagining the art worlds we inhabit (across galleries, museums, universities). As you put it, from memory, if you live on the borders of society, you rely on yourself to forge a space for yourself. Through the microcosm of the self, new worlds can be made.

Verónica Tello is a Chilean-Australian art historian and writer. Her research focuses on transnational art histories and their archives in the Global South.

All images courtesy and © the artist unless otherwise stated.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material.