Jeff Khan Your work often incorporates your own presence—it is either directly visible through the placement of your body within the frame, or implied through other kinds of interventions. For me, this feels like a drive to complicate the supposed objectivity that has long been associated with photographic images. Can you tell me a bit more about this drive in your work, and about how it plays out in Ecdysis (2019-21) in particular?

Cherine Fahd By being in the frame, I can visualise an undoing of the convention requiring the photographer to stand behind the camera. I can also capture the processes of portraiture. Rather than stand behind the camera, I like to be with the subject in front of it. Although I may be hiding behind something or someone, this simple move from behind to in front changes relations. The portrait goes from being about someone to being about the photographer and subject coming into contact.

I think when you point a camera at a person or a thing that pointing entangles you (the photographer). For example, we assume that the portrait is about the person it portrays. I don’t think that’s the case at all. The photographer brings a viewpoint and an agenda.

My drive isn’t to complicate objectivity as much as responsibility. I have a responsibility to show up, to know how it feels to be in front of my own lens. Before I point a camera at another person, I must be able to know how it feels to be photographed by me. Have I subjected myself to my own demands? Photography, rather than the photograph, is about that contact.

Jeff Ecdysis began with your call-out for participants. What were you seeking with this? Can you describe that process, and offer some reflections about the response?

Cherine I made a call-out on Instagram in 2019: “Wanted: women with dark hair and dark eyes to collaborate with me on a project.” It was the first time I have done that. I usually work with people I know: friends, family, and colleagues. For Ecdysis, I wanted to continue to do that, but to add strangers to the mix. I worked with strangers in my very first project, Operation Nose Nose Operation, in 1999 in Beirut, Lebanon. But I hadn’t done so since. I needed a lot of women and the call-out for dark hair and dark eyes was a way of asking for women to be my double and the darkness was a stand-in for racial appearance.

For weeks I received messages from women wanting to take part. I got a little notebook and started making appointments. Each portrait session was like planning for a date. Of the forty-four participants, twenty-three were new acquaintances. It was a somewhat random process – some women were Instagram followers, but others had received the call-out from friends. Daughters brought mothers and mothers brought daughters. Friends came with friends and relations. It was an extremely sociable process.

Jeff The way you filmed each portrait involved yourself and each subject performing the action in front of the camera, for three minutes at a time. In this situation, the camera becomes a surrogate for both yourself—the artist, creating the work—and for the viewer of the work. The uncanny effect in the final portraits is that each subject seems to be gazing directly at us as we watch them struggle with you. Did you have a conscious intention in setting up this dynamic?

Cherine Their ‘gazing’ at you, the viewer, was intended. I worked this out when I filmed the first woman, Sophie, my cousin. On holidays from university, I asked her to help me to nut the performance out. During the first performance I gave her little to no instruction on where to look. When we watched the footage back, she was looking all over the place, a bit lost. She looked at her hands and downwards mostly, but in an instant, she looked up and made eye contact with the camera. In that second, she was commanding. Her look uttered, ‘I see you seeing me.’

Jeff And did the resulting video portraits reveal something to you that you hadn’t consciously intended or anticipated at the work’s inception?

Cherine Making portraits with people always reveals something unintended. I welcome this above all. What I love about working with others is what they bring to the project beyond my authorial control. Collaborating like this opens my work up beyond my initial idea. This ‘opening’ produces knowledge. As such, each of the women ‘felt’ different to touch. When I sat behind them and rested my head on their backs to begin wrestling off the jacket, I was attuned to my body feeling their movements and rhythms. There were ripples, textures, flutters, pauses, for example. In the three-minutes, I could register hard, soft, strong, weak, light, heavy, unmoving, wispy, giving, taking, wanting, needing, free, constrained, at ease, guarded. Are these ‘moods’? I work iteratively. With each repetition I gather more information, more knowledge, more understanding of what I am doing. What I understood after forty-four repeats is that being two bodies entangled in a game for three minutes is different every time. And it is as much about what the camera captures as what the camera fails to capture.

Jeff The central premise of each portrait, the subject’s struggle to keep the jacket on while you attempt to remove it, is imbued with a sense of subtle violence. But it also strikes me as quite tender, a kind of symbiosis between tension and release.

Cherine I became aware of this in time. I didn’t start the project thinking ‘I want this to be both tender and violent,’ but I recognised that was how it read. The first four performances, with Sophie, Serina, Gilda (my mum), and Emi, revealed this. At first, this bothered me. I didn’t want the women to look (or feel) violated. Tenderness I am at ease with, but the violent gesture made me uncomfortable. But I also understood that it was implied subtly in the struggle and that this ambiguity was the strength of the work. I also realised that the three minutes we performed was the duration of a boxing round. I love boxing as a sport – not watching it as much as doing it. I used to box for years, not fighting, but sparring. At the school I trained at, we sparred in a ring for three-minute rounds. For ninety-minutes, we would rotate through the group of about six to eight boxers, fighting each other for three minutes. It was tough and affectionate, never aggressive, always controlled. That is what Ecdysis is. Exacting and restrained.

Jeff The installation of Ecdysis magnifies each portrait to substantially larger than human scale. The subjects tower above us, in a way that for me brings to mind ancient statuary—images of gods and warriors from classical mythology.

Cherine The scale performs a deification. I want each of the women to appear larger than life, to tower over us in all their illuminated glory. At that scale everything is amplified – their vulnerability, strength, eroticism, uncertainty, resistance, and willingness. Also, the entangling of two bodies was influenced by my travels to India in 2018. Everywhere I encountered images and statues of Hindu gods and goddesses. I was drawn to their many arms. I wondered what it would be like to have a multitude of limbs. I’ve often thought I would like to have two pairs: one pair of arms to function in the world, to be the doer, and the other pair to hold onto me, to act as the arms of care to keep me safe.

Jeff Ecdysis commenced prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has since complicated all of our physical and social relationships, especially as they relate to touch and its (now lengthy list of) discontents. Has our post-pandemic reality changed your view of the work? And how has it influenced subsequent works you’ve created?

Cherine Ecdysis performs contact through physical proximity and emotional distance. The bodies are in close contact, but the faces move in and out of ambivalence. It’s strange how the pandemic, especially social distancing, has exaggerated the contact aspect of the work. Given we had to postpone it and then cancel the live performance because it exacted too much contact between my body and the bodies of strangers, it’s hard not to read the work through the pandemic lens.

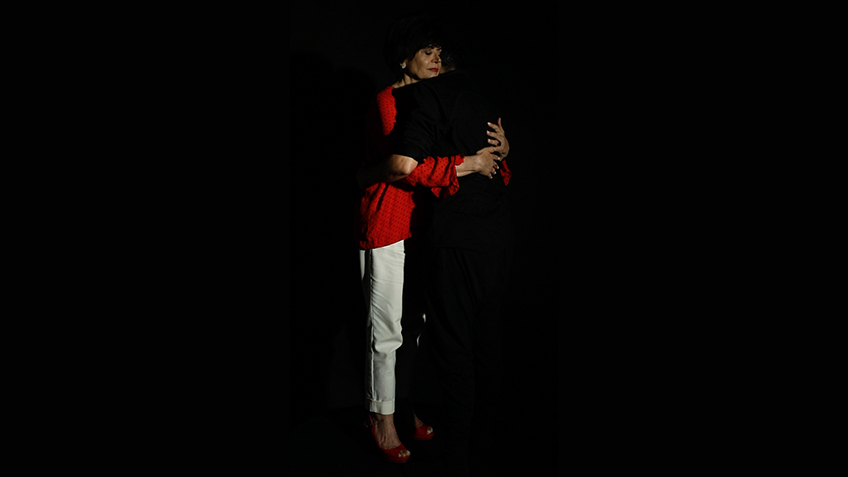

Certainly, Ecdysis has influenced other works, like Held (2021) and A Proxy for a Thousand Eyes (2020). Both of these works are interconnected with Ecdysis. Held is a ten-channel video work where I can be seen embracing other people. We stand on a rotating stage like statues. We hug – that’s it. The chiaroscuro lighting illuminates us as we turn. Again, a simple gesture made meaningful by the elimination of close contact during the pandemic. Held visualises my longing for the embrace of those I love, but also the inadvertent touch we receive from strangers on the bus or at a party on the dancefloor.

A Proxy for a Thousand Eyes (2020) was developed for the Sydney Opera House in direct response to the pandemic and to the social distancing protocols. You were part of that performance, Jeff. Despite the plastic that separated us, we were able to act in ways we otherwise wouldn’t. For example, we kissed tenderly on the lips and rubbed noses. Had the plastic not been between us, would we have done so even in ordinary times? Performing with others, in close contact, seems totally reckless in these times, whereas pre-COVID, it was built into performance. By that, I mean that the body and performance are inseparable.