‘Visibility is a trap’ – Michel Foucault

Internet narcissism, corporate surveillance and the manipulation of social media algorithms are touch points for Cinopticon – Giselle Stanborough’s immersive performance installation in which audiences see their reflection in unpredictable ways. The most unpredictable being the manner in which we now find ourselves, at home and socially distant, seeing Cinopticon from afar.

Cinopticon contemporises Foucault’s theory of the ‘panopticon’, a model of surveillance where the few watch and control the many. Today, with technology at our fingertips, we watch each other.

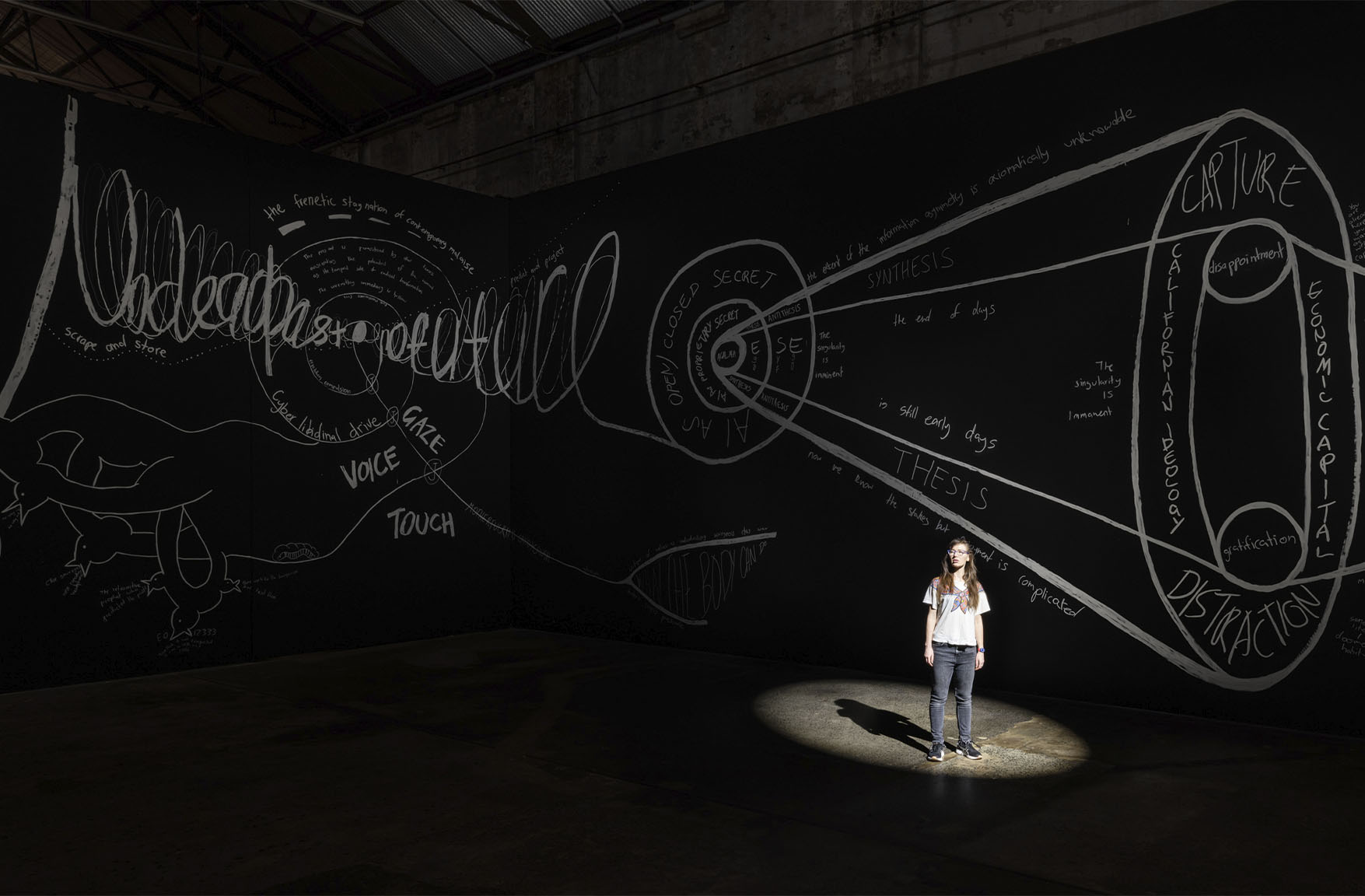

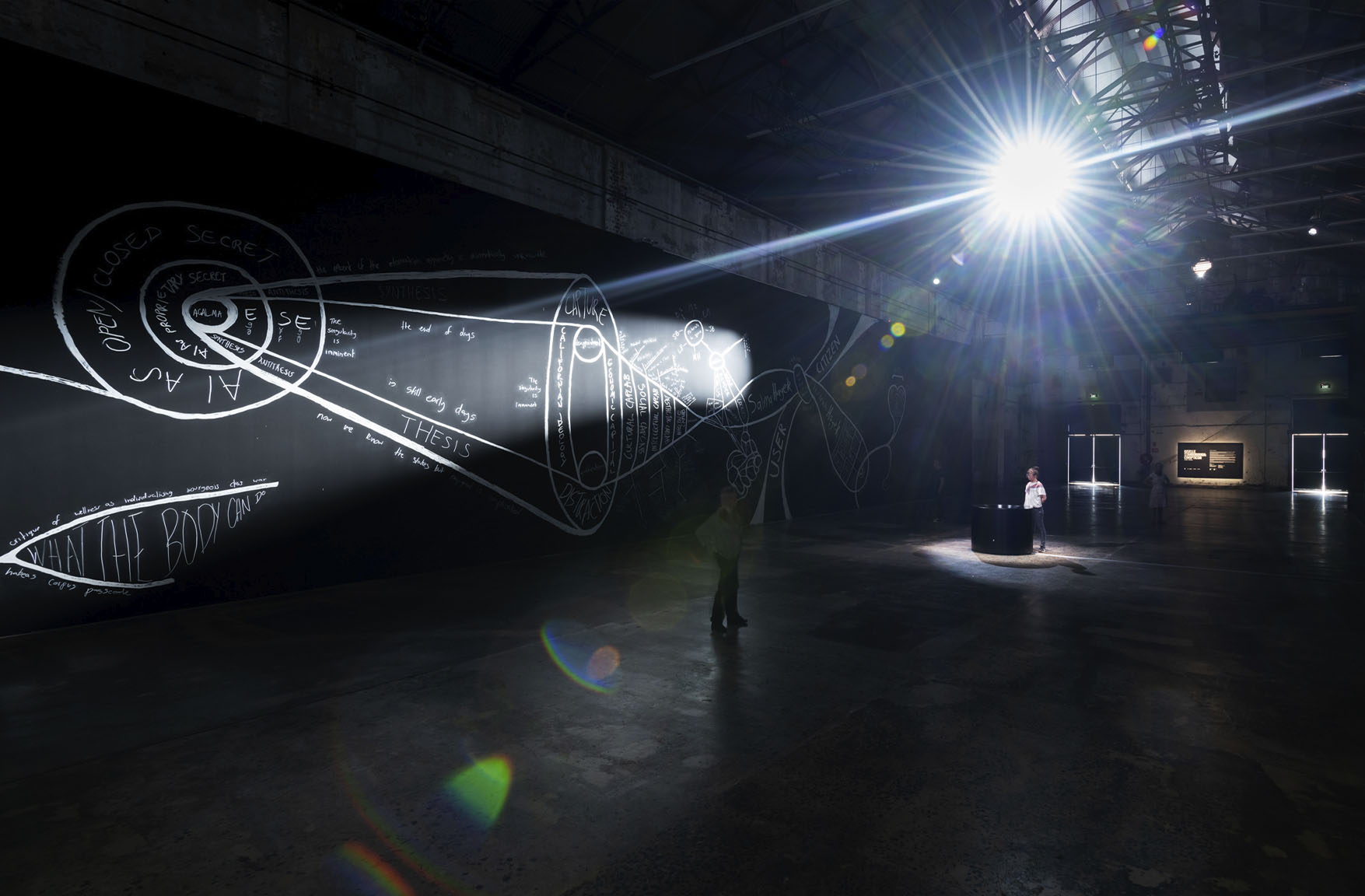

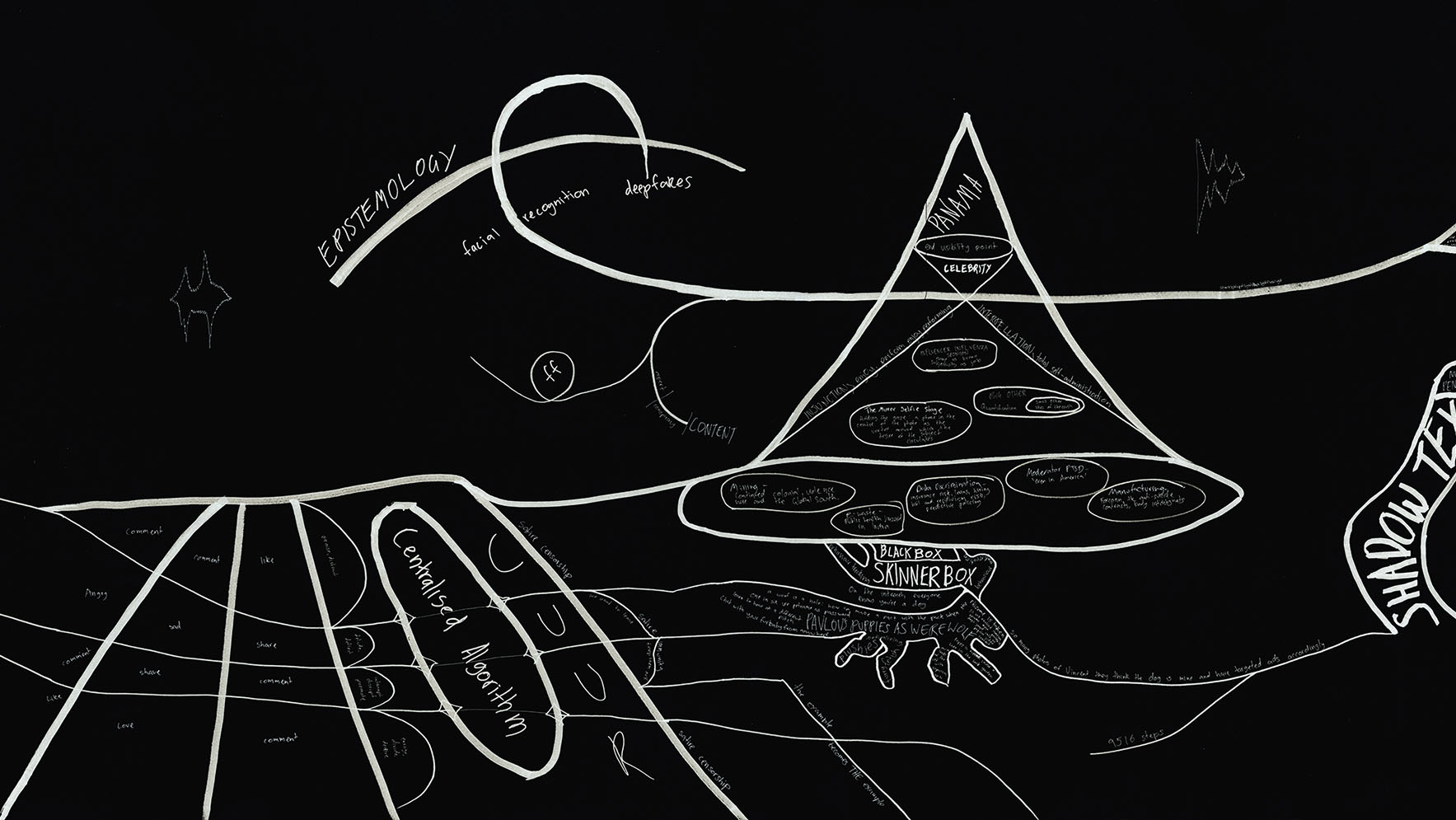

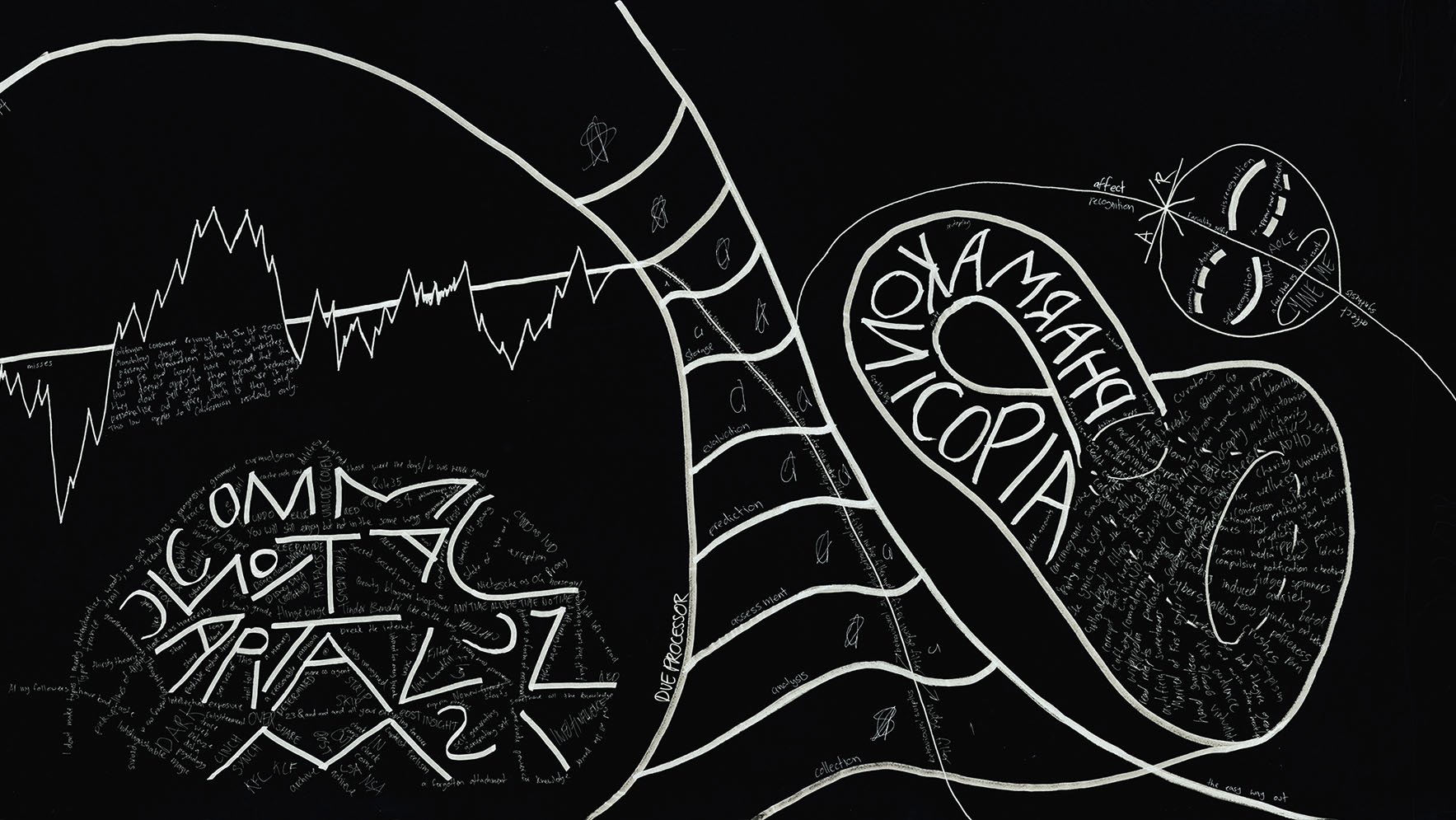

In Cinopticon various elements are abstracted through a prism of self-reflection. Motivated by the collapsing distinction between the public and private realms of contemporary life, Stanborough creates an unsettling and strange environment activated by image, sound and light. At the heart of its sensory quest, Cinopticon probes what it means to be watched and watch others.

Searchlights, sculptural forms, colossal wall diagrams and mirrored digital surfaces reflect the performative experience of social media platforms that have shaped the logic of the work. Through seductive video self-portraits depicting the artist’s fetishised body in pieces, Cinopticon draws attention to the way stimulation is aroused by the gaze, the voice and the body. As the subject and object of her own system of visual scrutiny, Stanborough is the ghost in her own machine. She haunts its house of mirrors, trapped as a digital apparition at the bottom of the well.

Giselle Stanborough is a Sydney-based artist whose work is concerned with the relationship between connectivity and isolation. Over the past decade, she has fashioned a unique practice that addresses how user generated media encourage us to perform notions of the self. Stanborough tackles contemporary interpersonal experiences in relation to technology, feminism and consumer capitalism. Cinopticon is her first solo exhibition in a major public institution.

– Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Curator and Carriageworks’ Director of Programs

Cinopticon (Well) 2020

Single-channel Full HD video sculpture, 16:9, no sound, 3:55 minutes

90 cm x 120 cm

Everybody thinks of Narcissus as a cautionary tale about vanity but it can also be read as a warning about the limits of alienation and selfhood. Maybe it wasn’t that Narcissus was in love, diving in to embrace his own reflection and drowning. Maybe he was the OG Lacan and saw that his ‘self’ was irreconcilably spilt forever. Perhaps being the first to theorise the “Mirror Stage” was too much, so he decided instead to destroy himself in an act of divine violence. Narcissism has never been about self-adoration for me, that has always seemed counterintuitive. To me, it has always been a story of self-alienation.

On the other hand, what if you were Narcissus and you peered into the water and there really was someone else there. In the sculpture, mirrored film is applied to the screen, which is set within a well. Looking in you see your reflection in my mouth. It speaks, or tries to speak, but you never know what it is saying. It is a silent call.

– Giselle Stanborough

Cinopticon (Voice) 2020

Soundscape

42:23 minutes

It is the experience of being online, without the visual stimulation. It is like scrolling through content on a feed or flicking through multiple tabs. Like all social media, it has a condensed temporality, and mimics those platforms structurally.

Throughout 2019, I was into the social media app TikTok. On TikTok, the sounds are decontextualised. What is interesting about the recognisable soundbites on Tiktok is that they are repositioned into a personal narrative. A soundbite from the Kardashians will be repurposed by a kid working minimum wage at Starbucks. As the sound piece itself states: ‘I am an anonymous subject, and the discourse merely speaks through me’. On one hand, TikTok is deeply anonymising, on the other it is deeply individualising.

Some of the content in the sound piece is personal, some of it is pop, and there is not a clear line between the two. There are comments and texts that I have sent or posted, recited verbatim, like ‘I won’t drunk text you, I don’t love you like that anymore’. Other content includes comments and texts I have received, some is taken from my iPhone Notes folder, while other parts are from my own internet browsing, describing IG ads or segments from newspaper articles and academic journals.

Under the gaze of surveillance capitalism it is not only what we produce but what we consume that individualises us. Our watching is a kind of becoming, but not a liberating one. It carves out who we are, which impacts the kind of content we are fed, which in turn impacts who we think we are and what type of place we presume the world to be. It is a feedback loop where we are being produced as we produce the data that in turn produces us.

– Giselle Stanborough

Cinopticon (Wall) 2020

Wall painting

7341.20 cm x 642 cm

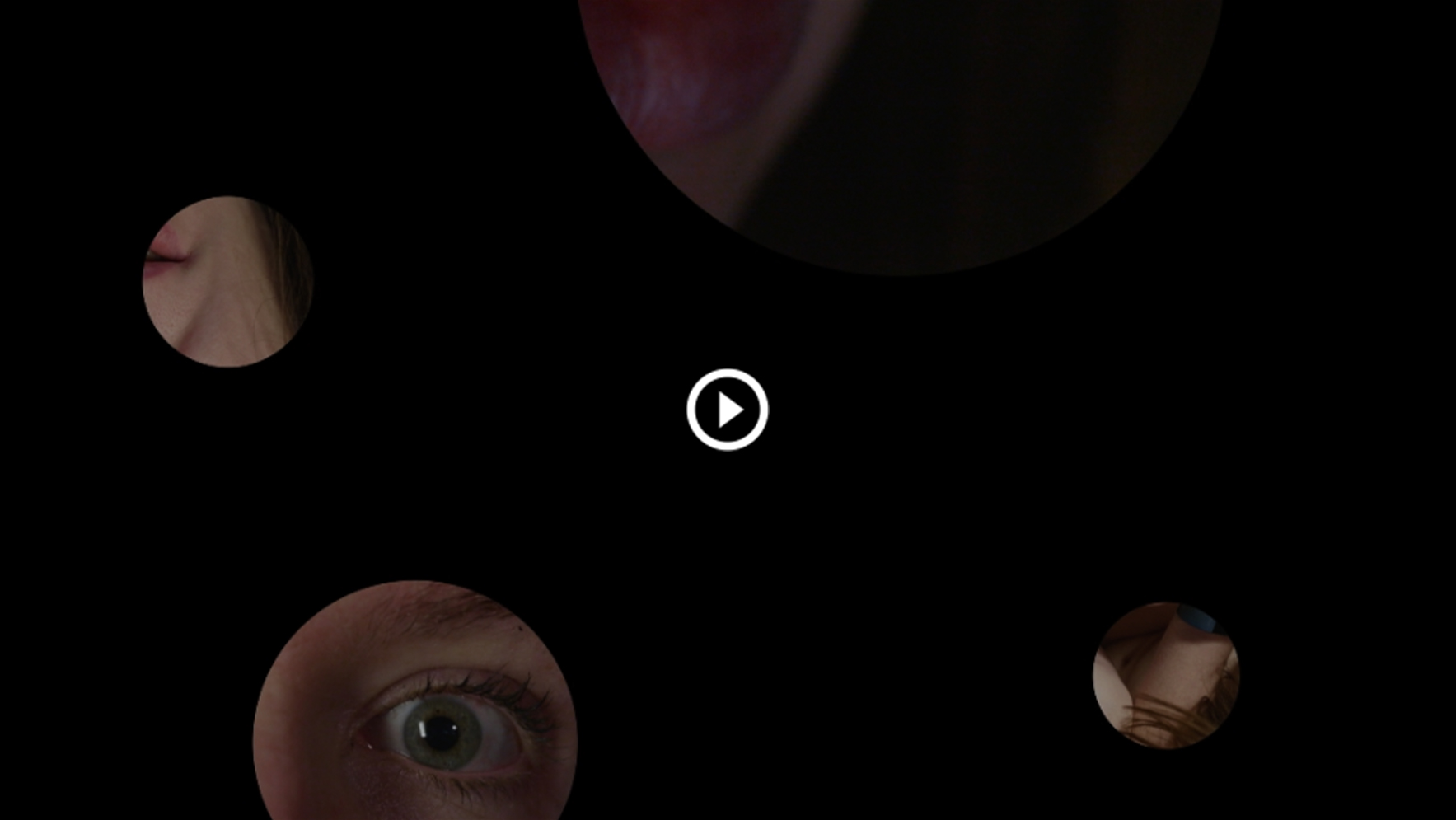

Cinopticon (Mirror) 2020

Single-channel Full HD video with mirrored film, 9:16, no sound, 5:00 minutes

I spent my adolescence on 4chan and for a while, there was a popular image editing request called ‘bubble porn’, which would sexualise images through the insertion of a ‘bubbled’ negative space. This was my first experience of the idea that desire comes from an absence, which I would come across later in life when I became interested in Lacanian psychoanalysis. Bubble porn artificially infuses a sexual gaze by inviting an imaginative, lurid ‘filling in of the blanks’.

The functionality of the mirrored film on the screen is such that the ‘blank’ pixels, reflect the ambient light of the room and the pixels that are ‘lit’ reveal the image on the screen. In this work, the negative ‘bubbled’ space is where you see your own reflection, as in the case of the original bubble porn, it is your libidinal imaginings that fill the negative spaces.

Lacan describes the “Mirror Stage”, the stage at which the infant recognises themselves as themselves, as being necessarily narcissistic. Here, my own segmented body appears, disrupting the narcissistic enjoyment of the viewer. The segments of my body are as awkward and unflattering as they are erotic. Peeking in and out of the shots, as if it were an accidental inclusion, is the Fitbit. The wearable device is the emblem of our alienation from our own body. Perhaps the success of consumer biometics is not, despite the fact that we are made legible to power, but because of it. We are threatened, oppressed and exploited by the very thing we desire: to see and be seen.

– Giselle Stanborough

Following its installation in March 2020, Cinopticon will be physically unveiled to the public for the first time when Carriageworks reopens Friday 7 August.

Visit Cinopticon

Cinopticon is presented as part of Suspended Moment: The Katthy Cavaliere Fellowship, a suite of three unique commissions to support Australian women artists working at the nexus of performance and installation. The series is a partnership between the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne; Carriageworks, Sydney; and the Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart.

Curator: Daniel Mudie Cunningham

Project Team

Assistant Curator: Aarna Fitzgerald Hanley

Exhibition Manager: Glenn Thompson

Production Manager: Todd Hawken

Artist Collaborators

Lighting Designer: Fausto Brusamolino

Videographer: Emma Paine

Video Editor: Elliott Magen

Colourist: Justin Ngy Tran

Artist Assistant: Megan Monte