As part of The National 2021: New Australian Art exhibiting artist Alana Hunt will be Carriageworks inaugural Writer in Residence. Working progressively she will publish Conversations and Correspondence—six texts that take as their starting point the bodies of work All the violence within this and In the national interest both exhibited as part of The National.

For the fifth in the series, Tensions, Alana Hunt is in conversation with Kush Badhwar—an artist and filmmaker operating across media, art, cinematic and other social contexts.

Kush Badhwar: A question I had—because I haven’t been in the exhibition space at Carriageworks—is that, with your images and the install, they are two separate but connected series, but they’re displayed back to back?

Alana Hunt: Yeah. There are three double sided light boxes placed on the ground.

Kush Badhwar: Immediately in the display, a connection is formed but it’s also a connection in opposition. Do you want to say something about that?

Alana Hunt: It’s funny you start with that. I feel a bit goofy saying this, but making exhibitions or working out how to put my work in exhibitions is actually a part of my practice that I feel least confident about. And I think it stems from the fact that during and after my undergrad I became really interested in the public sphere, and the idea of art as a social catalyst rather than an object. The expense of putting on exhibitions that were ultimately reaching only select audiences, was also a major deterrent. So instead, I put a lot of energy into working out ways to circulate my work outside of galleries, in less expensive but more engaging ways. I’m not at all opposed to exhibitions but I am often really inspired by practitioners who don’t always work in exhibition contexts. Like Sanjay Kak, for instance, who makes documentary films, writes, edits and publishes books, and also sometimes exhibits. But is really engaged with much broader cultural and political ecosystems. And before I encountered Sanjay’s work, I was familiar with Raqs Media Collective. What inspires me most about Raqs is the fluidity with which they approach their practice—it’s not practice and research or making and theory, publishing or curating. For them, it’s all one thing that they “do”. Ross Gibson has also been someone on my horizon in this sense too—working over many years and across mediums and disciplines in unique ways.

But what I’m saying is over the years I’ve put a lot of energy into thinking about how to get my work moving outside of exhibition spaces. So when I come into exhibition spaces, I often feel quite uncertain. And I guess that’s part of what these conversations are about as well—bringing broader elements of my work in The National, and what the work can be a catalyst for, into the exhibition, while extending the work, in a way, beyond the physical and temporal space of the exhibition too.

What I’m photographing and thinking about at the moment within and outside of this exhibition, is all part of a broader attempt to examine the violence of settler colonialism where I live; how that violence unfolds every day; how entwined we are as non-Indigenous people in that violence; how blind we are to it; and how inescapable it is.

This work began with the colour images—All the violence within this—looking at a certain culture of leisure that so many of us strive for. And how that culture moves on stolen Aboriginal land in Australia today.

I also found myself looking at gravel pits—quite small-scale mines that are everywhere up here, but seem to be obscure, not often noticed. What’s extracted from these pits is basically used to make the roads that then enable us to travel to these places as tourists.

In a sense, these two subjects began to feel like two sides of the same coin. One a world of abundance and leisure, the other a barren, broken, tortured Country.

Kush Badhwar: These thoughts about leisure were echoing in my mind when I was traveling recently, thinking about your work on the way and seeing things that might connect to certain attitudes I’m seeing in Europe. For example, in the train, the toilet was wallpapered on all sides with mountain scenery. Another statement I saw in Munich Airport read, “Enjoy all the beauty of nature in VR,” in virtual reality. It struck me as a strange statement.

Alana Hunt: I wanted to ask what you think about the value of exhibiting as an artist? You seem to invest in different places in quite political ways through your work. Something that resonates with me. And I’m just wondering, in that context, how do exhibitions feel to you?

Kush Badhwar: Similar to what you described. Exhibitions are often a byproduct of other stuff that is going on. Somehow there’s still a relationship between the two, work in and out of the exhibition. Sometimes the exhibition produces the currency to enable the other work. Sometimes it’s a space to try something out. Often it’s awkward.

Alana Hunt: I think there can be powerful moments in exhibitions. But immediately after the opening of The National, I did feel a little bit deflated. Just thinking about the amount of energy and resources that go into making an exhibition like this, and then the movement of people through the exhibition space itself feels so brief. People might give your work 30 seconds or, if you’re lucky, maybe 60 seconds, I don’t know.

That said, as The National unfolded over a few months this changed. Time is important. I received quite pertinent responses from a number of people who had really been impacted by the work, both via the exhibition and these commissioned texts which bounce in and out of the show, and around it. While the texts are also continuing after the exhibition has closed. There is a symbiotic relationship there. Together this has opened up numerous other points of engagement (often out of public view) but still unfolding within the work—things neither the exhibition nor the text could do alone. This has felt like something much more solid, and in a sense growing.

I tend to think of exhibitions as one avenue among many. They can be a great space for work, and they can be an average space for work, but they definitely don’t need to be the only space for work.

Kush Badhwar: I often feel the same, except with this exhibition that’s happening at Tiroler Kunstpavillon. As you’ve probably noticed, post-COVID, the screen seems to have become an important exhibition site. So if you’ve got ready work that can be shown on the screen, a film or something else, it becomes easier to exhibit that kind of work. But as I developed work for this exhibition, I realised what came together doesn’t translate in a recording, it can’t be documented properly. It’s just coming together for this moment. Then I was like, “Oh, this is what it’s about—things can come together in this delicate fashion that can’t happen otherwise.” It felt strange to realise this in COVID times, when COVID is asking for not-that-type of exhibition.

Alana Hunt: Definitely. Say with the images that were in The National, it’s one thing to look at those images on a screen, but it is another thing entirely to see them as one-metre-high light boxes that you’re actually physically walking around and feeling implicated in…There are indeed certain things exhibitions allow for that can’t be attained in other contexts.

But to jump to one of these other contexts—can you talk a little about Ulwe Hill? Is it still a hill?

Kush Badhwar: Maybe half a hill. It was around a hundred metres high and at this stage it’s maybe half the height that it was. It’s part of the Western Ghats, which run along the west coast of India. About half of it is in the area under construction for the Navi Mumbai International Airport and the other half was being quarried even before the airport construction began.

Wetlands surround the hill. They’re in the process of bringing the hill to zero, and laying the stone that the hill consisted of on top of the same area that it occupied to increase the height of the area to about five metres above sea level to try and avoid flooding. So the hill goes from a hundred metres to five metres spread across the area. And then on top of this, they plan to make this Zaha Hadid Architects designed airport, which is intended to serve as Bombay’s second international airport.

The airport was proposed in 1997. In 2007, they got the clearances to go ahead and in the last few years they’ve started preparing the ground for it. On what’s now the airport site, there are, or were, ten villages, which are at a later stage of relocation. In these villages, you have 3,500 families who are predominantly from Agri and Koli—farming and fishing—communities, who have or are being relocated, geographically not so far away, but further from their traditional livelihoods.

Alana Hunt: I’ve read a little bit about this through your work. And it got me thinking about the role of…I don’t actually know what is a good word for what I am trying to refer to. I’ve come to my practice as someone who was really interested in film very early on. And then I became interested in what has been termed participatory art or social practice or relational aesthetics or new genre public art, whatever those various terms have been within the art world. But then I’ve also found myself pulling back from some of the methods or formulas that are placed around things like “community engagement”. Those terms don’t really resonate because they often don’t feel lived. I feel like I pick up on some of these currents I am trying to describe in your work, through Ulwe Hill and your film Blood Earth. In this work there is a sense of relationships—a point of engagement or a social process that feels important, but maybe not always explicitly at the forefront of the elements that become public. Does that make sense to you?

Kush Badhwar: Absolutely. I mean, there’s also a discomfort with those terms, but there may sometimes be engagement with some of the ideas that underlie or travel through those terms. In the case of the airport and Ulwe Hill, there was already an engagement going on because I’ve been living in Navi Mumbai for the last, I don’t know, I guess it must be around ten years by way of my partner who grew up there. We’d been engaging with the area and in the course of these engagements, the airport kept popping up as different kinds of anomalies—sometimes sold as a dream on billboards, at other times curiously absent from the environmental conversation in the city. It felt like a glaring hole—what is going on there?

It felt necessary to look at the history of Bombay. The city of seven islands, when the British administration came up with this plan to “reclaim” the land in between these seven islands and turn it into a peninsula. As migration into the city increased, there were perpetual struggles to accommodate, or restrict, people. In 1965, in an edition of the art magazine Marg, architects Pravina Mehta, Charles Correa and engineer Shirish Patel proposed New Bombay, a satellite city across the harbour, to alleviate the city’s space issues. From this magazine, the idea gained traction and New Bombay began construction around 1970 and people moved there from different parts of the city, the state and the country. But as with a lot of such projects, the new city never seemed to meet it’s ideal. Over the course of time, there seems to be a negotiation with the shortcomings of the city embodied in people’s existence. Sometimes, negotiating these shortcomings is expressed by pinning hope on large projects, like this airport, as though these projects could finally make our city what it was meant to be.

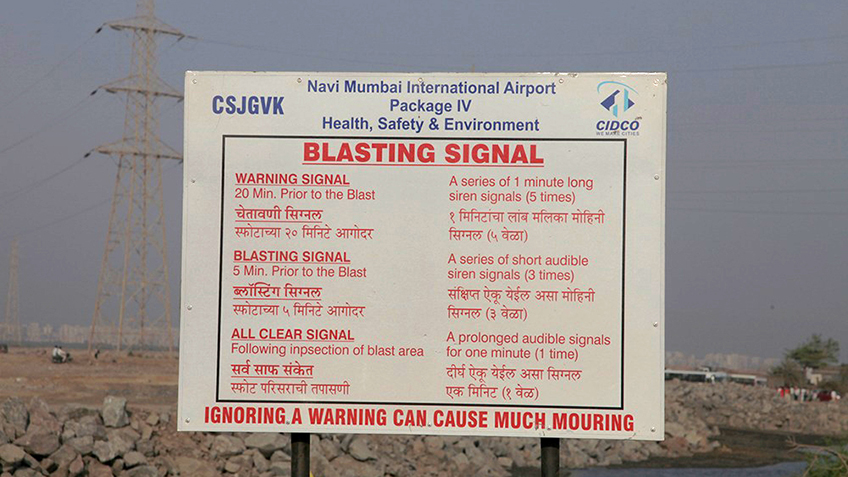

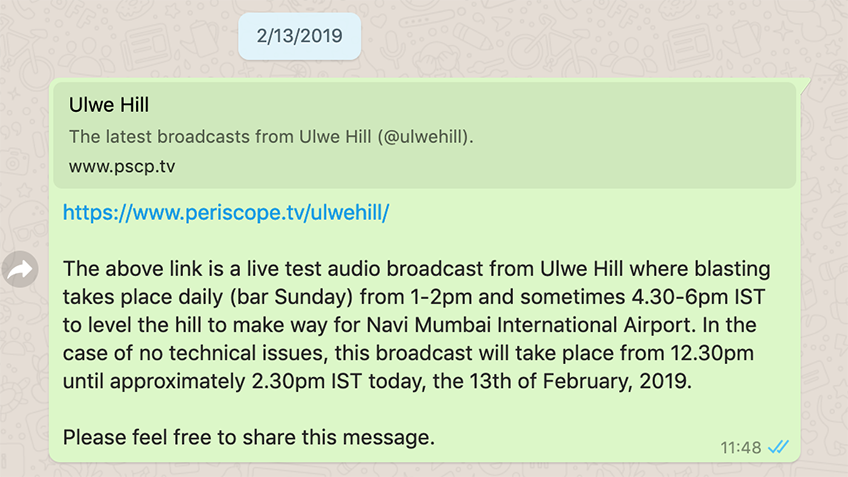

One of the things I encountered when I started visiting the airport site were these explosions that would take place daily, sometimes twice daily. I was thinking that surrounding the airport on all sides there seems to be this discourse that “this airport is going to make our city better” and on the other side there are these explosions. So I thought, what if the explosions are heard where we live? What might hearing them do to the idea about what this place could be?

Alana Hunt: And what happened?

Kush Badhwar: I attempted a broadcast and sent a WhatsApp message for people to tune in live, which some people did. It started some conversations and led to collaboration with CASP (Council for Art and Social Practice) and the filmmaker Anant Jain. But it also made me realise how technically challenging it is. I was using my mobile with a basic internet connection. The phone kept heating up and shutting down, the internet connection kept crashing. I realised that a continuous broadcast of the audio, which I was initially trying, was not working with what was available to me.

That’s where the Five Million Incidents exhibition came along and I thought, “Maybe this can help me overcome these technical issues that I’m facing with this idea.” And then it just went in other directions after that. While Five Million Incidents was valuable, at the same time, there was awkwardness in terms of sharing the work outside of the neighbourhood or the city, though I was conscious that people living outside Navi Mumbai may use the airport in the future if it comes into being.

Alana Hunt: I know every place has their own uniqueness, but I find so many resonances in hearing you talk about Navi Mumbai, as a new city that was created in the 1970s and never lived up to expectations. The town of Kununurra that I live near, was similarly created in the 1960s and 1970s, with the idea to shift the economy of the region from pastoralism to agriculture, in order to ultimately increase colonial control in the region through settlement. Up until this period the region had been occupied quite sparsely by colonists—single families operating huge cattle stations.

In the first half of the twentieth century the pastoral industry was falling apart a little bit, largely due to drought and poor markets. This, in part, prompted the idea of building a large-scale dam to irrigate a northern food bowl. We get eight or nine months of zero rain and then three to four months of a huge monsoon. There is this colonial desire to control the water, to contain it, to put it to what those in positions of power see as a functional use. This dream also led to blowing up a mountain in order to make a dam wall, now known as Lake Argyle. It was the largest non-nuclear explosion in Australian history. But in the process they destroyed and damaged the Indigenous food bowl that was already here—drowning a world—and further displacing Miriwoong people from their Country.

So the town of Kununurra was made to accommodate the farmers and their families, and all the related industries. The population of the colonists, of non-Indigenous people, flourished, and the displacement, and marginalisation of Miriwoong people on their own land only escalated.

As you were talking about negotiating the failure of the city, here that colonial dream of a food bowl, of a thriving north-west Australian settlement, is rife with stories of failure, sucking up huge amounts of government funds in the process. They’ve tried to grow lots of different commercial crops to varying degrees of success. Rice failed because swarms of magpie geese ate the shoots quicker than they could be planted. So this colonial dream never fully reached where people thought it would.

I most often see these things here, through the lens of settler colonialism, but it is also tied up with things like urbanisation and modernity, and neo-liberalism too.

I’m just wondering about this in the context of Mumbai or Navi Mumbai and in India more broadly. A lot of these things come out in Blood Earth where you’ve got the story of a community in Odisha being impacted by corporate mining. When I look at mining here, whether it’s the small-scale gravel mines that I’ve photographed or larger mines such as Rio Tinto’s Argyle Diamond Mine, I understand so much of this through the lens of settler colonialism. But then I feel there’s so many resonances with a lot of the things that you’ve worked on but in an apparently post-colonial and independent India. How do you understand this?

Kush Badhwar: There seems to be an increasing scrutiny of the term ‘development’, in terms of what constitutes development and for whom, even outside of activist circles and those directly affected by such projects.

Regarding settler colonialism, I’ve been coming across the term through your work and in some other contexts, but it’s not one I hear often, at least in whatever I’ve accessed through the Indian context. But in many ways it does seem relevant and I’m interested to see how it works or doesn’t as a term or an idea in that context as well. In Navi Mumbai, I feel something along those lines operating, evident in certain divisions in the place.

The city was planned by producing neighbourhoods in modernist grids in proximity to the pre-existing villages of the area. The villages still exist—over the course of time they’ve taken on qualities of the urban, but have urbanised in different ways to the places made according to the plan. The villages are referred to as gaon, which literally means village, and the grid-based neighbourhoods are referred to as nodes or sectors and the divisions between the two are palpable. Those that inhabit the nodes or sectors, for the most part, have come from other parts of the city, the state and the country, some of the attitudes and behaviours at play could perhaps be described as settler-colonialist.

In the last few years, there’s been robust expression of discontent around various aspects of the city. Though there are overlapping concerns across various movements in both the villages and the sectors, the nature of the expression feels divided along the lines that Navi Mumbai was planned or conceived.

Alana Hunt: When I first moved to the Kimberley in 2011, I was working at Warmun Art Centre, and through that I would often encounter the community relations people from Rio Tinto, who would visit to talk to the senior artists and community members about the mine. I had just moved back to Australia from Delhi when I started working there. And I met this Indian girl who was working alongside the community relations guy from Rio Tinto. I was curious and got talking; she’d studied social work at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai (TISS).

Kush Badhwar: It’s quite close to Navi Mumbai.

Alana Hunt: That’s where all these subtle connections are. So, she had studied social work at TISS and landed this internship with Rio Tinto who had brought her to the Kimberley in Australia to show her how to develop “good” relationships with Indigenous people. So then, she could go back and model that through Rio Tinto’s work in India with Adivasi people.

It really spun me out at that point in time, because I had not long moved back from Delhi, where I was aware, not deeply, but broadly speaking, I was aware of the internal war that India was waging in the mineral and resource rich Adivasi regions—driven by corporations wanting access to Indigenous lands. Operation Green Hunt began when I was in Delhi. And suddenly, to see this girl here in Australia, for this purpose, really spun me out. It made me realise that there are far more points of connection than we’re aware of.

At that point in time, Rio Tinto was modeling these supposedly ideal relationships with Indigenous people in Australia. Over the last year with what happened with the Juukan Gorge destruction, the fallacy of that is starting to unravel.

Yesterday, on the radio, I heard Eastern Guruma people in the Pilbara have cancelled all meetings with and welcome to Country’s for Rio Tinto, in response to the revelation that Rio Tinto threw cultural artefacts belonging to the Eastern Guruma people into a rubbish dump in the 1990s. And then proceeded to pursue good “community relationships” to enable mining to take place. The journalist interviewing the spokesperson asked, “What does that mean to withdraw a Welcome to Country?” The spokesperson said, obviously it’s a way of saying that you’re not welcome here. But it’s also a way of saying we’re not pretending things are ok any more.

This is a powerful form of protest in a context of where the bureaucracy at hand is constantly working to obscure, or quieten, or silence, or delay, or postpone, or weaken the voices and opinions and authority of these Indigenous people. And for that to happen during NAIDOC week in Australia, to a large corporation, who’s already received a lot of public outrage over the last year with Juukan Gorge, it felt like something quite important. It also made me think about the different ways people are able to enact their authority and strength, and what mediums we have at hand to do that?

Kush Badhwar: Sometimes the symbolic nature of protest—what is being articulated, when, and why—is lost when people insist on seeing things only from their own perspective.

What might be Navi Mumbai’s largest protest happened a couple of weeks ago. The various Agri and Koli communities came together to argue what the airport should be named. They want the airport to be named after Dinkar Balu Patil, a politician and activist who fought for their rights when Navi Mumbai was coming into being. The state, however, says the airport should be named after Bal Thackeray, the Shiv Sena politician.

People affected by the airport project have already gone through so much pain…You can imagine the negotiation processes with authorities completely depletes the energy that exists in oneself and as a community. And they’ve gone through years and years of this. I think they’ve come to a realisation that whatever they do the airport is going to come into being. Ninety-odd percent of their relocation has already taken place. So now that it’s at this stage, they are left arguing for the name. That’s what they want to argue for, but a sensitivity or an understanding of what people are saying seems to be lost, especially amongst the movements emerging from the sectors.

Alana Hunt: These long drawn out, exhausting negotiation processes, and the poor communication therein, happens all the time where I live. It has made me increasingly sceptical of the idea of ‘consultation’.

Sometimes, I get to be a fly on the wall of these ‘consultations’ because my partner, Chris Griffiths, is a Traditional Owner, and is often consulted about developments happening on his father and his mother’s Countries. I’ve sat in on meetings—when my father-in-law was alive too—listening to this communication take place. I see that painful, unceasing, life-draining bureaucracy play out. And that’s where a lot of my work around this comes from. It makes me angry and sad because I see it taking up so much of say, my father-in-law’s life and he’s gone now. And I see it taking up so much of my partner’s life. Unnecessarily.

Colonisation isn’t just an event. In Australia it materialises in our presence. Through the houses we build, the laws we follow, the roads and airports we make. The processes of consultation we establish.

Your work feels quite observational. It doesn’t feel like you’re—maybe I’m wrong—but it doesn’t feel like you’re making it to stop the airport at Ulwe Hill, or to sort of bring some resolution around what’s happening in Blood Earth. It feels like you’re observing, but in a way that is also very engaged and committed to these processes and the politics within them. You’re moving not so much to cause or instigate political change or to stop the events that you’re witnessing but to examine and understand them. Does that make sense?

Kush Badhwar: Yeah, I’m not completely sure where that emerges from. It could be a result of being born and growing up in Australia and how I fit in, or don’t fit into the mainstream of either Australian or Indian society. But also if you look at activism generally, you have these powerful figures who are doing amazing work. And it’s sort of knowing that I couldn’t do that myself. So it’s just finding a place where I can somehow be, amidst that.

Alana Hunt: Yeah, I’m not one of those people either, and so what you’re saying resonates with me. But I sometimes feel a little bit torn. With Kashmir, I was very clear from the outset that I wanted my work to reach people in Kashmir. I didn’t want to make work “about Kashmir” that was only seen outside Kashmir. So I used many things to do that—personal conversations, photocopied paper, the internet, the newspaper, and the format of the book.

However, where I’m living now, I’m taking these photographs and I’m writing and I’m making things, but I’m finding it harder to circulate this material where I live. It’s being published and exhibited elsewhere, but not right here. I think it will come over time, somehow. But it’s also a little bit harder here, the social landscape feels fragmented—I’m more isolated. The local social media groups can become racially charged really quickly. Sometimes I do feel tempted to intervene in that space in a really overt way. But then I feel like it’s also such a waste of space, it’s not a place to bother engaging with.

I think part of that for me, is similar to what you’re saying. On one hand, I’m so embedded here, but on the other hand, I also do not really fit. I mean, where I live I am with Aboriginal people all the time, but I am clearly not a blackfella. And I don’t really get the chance to hang out with whitefellas, for whatever reason. So that observational place that I see you occupy is something that I’m also finding myself in quite a bit too. It’s not an uninteresting place to be.

Kush Badhwar: Yeah, even in that place, I can see you’re aware you’re not operating in a vacuum.

Alana Hunt: And what about how you mentioned to me earlier that you grew up in the same area that Narelle Jubelin was speaking about in Relations, the place her video Ilford Colour depicts?

Kush Badhwar: Yeah, it was really interesting for me to see that. The only other thing I’d seen on screen from that part of Sydney before was Don’s Party.

There’s a few different lines of trajectory, but they’re not completely clear to me. I mean, one is that my mother started an Indian community newspaper in Australia in the mid 80s, so my outlook of Australia comes from that zone. At one level, my thinking responds to my parents’ lives and work, what’s going on in the community in Australia, rather than in Australia as this large monolithic thing or idea.

Alana Hunt: And do you think that Indian community that you grew up with had much consciousness of their role in the colonisation of Australia? Like could you, or could they, see themselves as colonists?

Kush Badhwar: No, I don’t think that they would see themselves that way. That consciousness is slowly starting to emerge, perhaps.

Alana Hunt: I mean, most white people don’t see themselves as colonists either.

Kush Badhwar: Absolutely. I think it works in the Indian context as well, in the sense that people who have been able to occupy positions of power, particularly as India became a nation, will separate themselves from colonialism even though the kind of attitudes and behaviors might be like that.

There’s complicated relationships with colonialism that run through my, and possibly all of our personal histories. In my case, both sides of my family came to Delhi as refugees due to the partition of India and Pakistan after the British left India. There’s a loss of being able to access where one’s forebears come from after an event like that. But it also allowed my parents to grow up in proximity to the institutions that emerge in the capital of a new country at a nascent stage. The proximity helped them access these institutions, first as an imagination then as a possibility to affect change in their lives, which enabled them to move to Australia after the White Australia policy was dismantled.

Alana Hunt: Right.

Kush Badhwar: And, like Narelle’s parents, allowed them to be part of that generation of “owner-builders” after they found their feet.

Alana Hunt: So your parents built on that land? They built the first house on that land?

Kush Badhwar: Yeah. My dad designed the house, did a bricklaying course at TAFE and then he and a few friends built it. It’s on Darug Country.

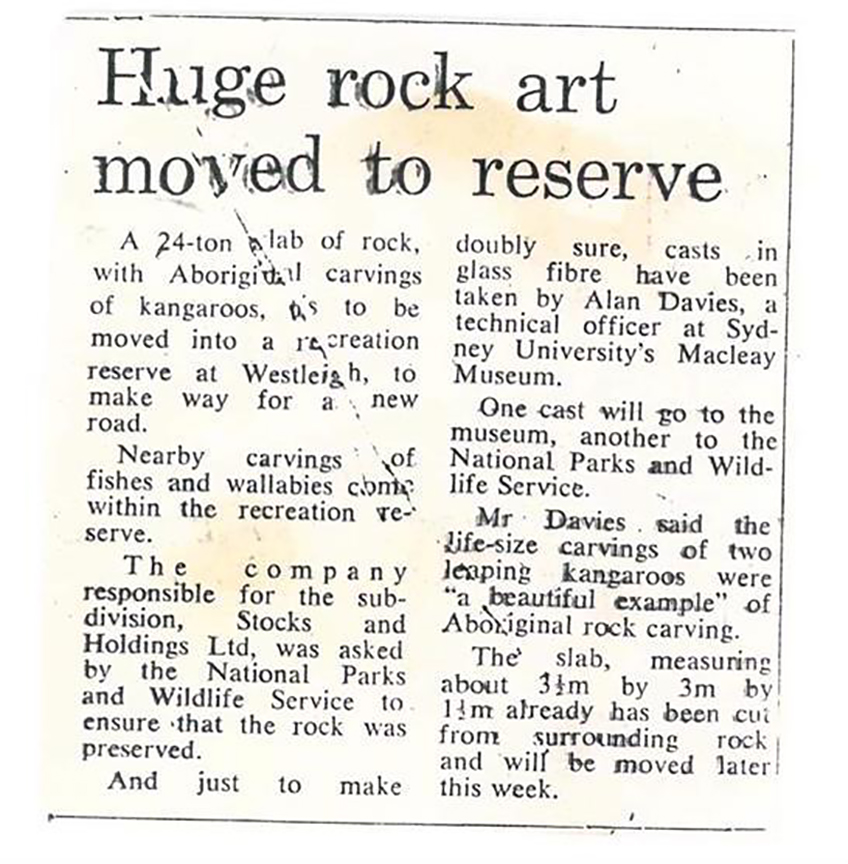

There’s Indigenous rock carvings in the area. There’s one particular rock carving, of two kangaroos. When they were building this suburb—it also transitioned from pastoral land into a suburb—they came across these carvings which they cut out into the size of a king size bed, and put on the edge of the road. It’s still there today.

Alana Hunt: Really?

Kush Badhwar: It’s literally cut out like a rectangular prism.

Alana Hunt: So you look at it when you drive past?

Kush Badhwar: A few steps off the road. They’ve made a small ramp so you can view it. But then there are also many other carvings that are not…

Alana Hunt: Cut.

Kush Badhwar: Not cut, but also not signaled or acknowledged.

I had this moment last year when I was in Sydney. If you look at this suburb, it’s built across a ridge, therefore the drainage water from all the homes goes down into the valleys. As you enter the bush from one particular point, there’s carvings in the stone of these fish. There’s homes that back onto this. And there’s this little pipe that comes out of the back of one of their gardens. The water comes out, travels down over this stone with the carvings of fish on it.

As I was walking past this, the person who owns or lives in the home was watering the garden. And so I was like, “Hi. I’m just wondering, do you reckon…” I posed it as a question. I was like, “Do you reckon the water from your garden affects the carving? And then he kind of just shrugged it off saying, “Oh, there’s nothing we can do about that.”

Alana Hunt: Wow. There’s so much you could do about that. Even with one pipe, it doesn’t even sound very complicated to just put an extension, like the same thing that hangs out the back of a washing machine and move the water a couple of metres away. But even beside that specificity, that’s the rhetoric of the whole settlement here, as though there’s nothing you can do about it, so we continue doing it. It’s so casual, and so violent.

When I spoke with Jazz Money, we spoke about impossibilities. White people often say, “Well, I can’t just go back to Europe.” Although that’s not really a possibility, it doesn’t mean that thinking about it and kind of finding ways to act on that thinking can’t be part of the equation.

Kush Badhwar: That reminds me of the images of your son. I’m not sure if this is the case for you or not, but there seems to be a lot of complicated vectors in those images. I’m using the word vectors. I’m not sure if I’m using it correctly, just in terms of mother and son, family, and then nation and all of these sorts of things that don’t feel resolved. They feel like they carry tension in the images themselves.

Like you’re infusing another history into these mines and into that area through these images, and it feels like maybe they’ll never reach resolution. I’m sure these tensions won’t be resolved. But they will play out in different ways over the course of time, as these images… as we go into the future.

Alana Hunt: I’m glad to hear you say that they hold that tension because that’s what I’m dealing with, this tension, across multiple levels. And I hope that keeps resonating. I’ve had people also say to me, people that don’t know me so well, “Oh, and here you’ve got a white kid running up this hill.” And on one hand, my son is really bright in his skin color, but his father’s Aboriginal. So he’s an Aboriginal kid and a white kid, all at once. This is not something I’ve really spoken about publicly, but his presence is multidimensional there. And very personal.

I didn’t originally think he’d become part of the work. I was shooting the gravel pit and he was running around and got in a few of my shots. I thought it might be nice to have a photo of him just for myself. And then when I got the roll of film back and I looked at them, I felt that he actually… He’s in three of them that I really like. And I think his little journey there, in that space is very pertinent. I think that image in particular is asking us how we’re going to navigate this broken world. But it’s also telling us, that we can.

Kush Badhwar: It’s these productions of tension that, for me, feel valuable. The potential or the possibilities that exist in the work are in producing tension. I can feel it in these images. I can feel something that I can’t resolve when I see them, but I can feel them there.

Alana Hunt: Yeah.

Kush Badhwar: Living in Navi Mumbai, I’ve seen different initiatives over the years that have tried to make galleries or other types of cultural infrastructure in the city, and they’re often fighting an uphill battle or failing.

The international airport in Mumbai has a massive collection of art, apparently over 5500 pieces. You can see that airports across the country are also producing galleries or museums.

The Navi Mumbai International Airport, if or when it comes into being, will probably have a gallery or be a big museum—it will probably be the one that finally succeeds in this space after all of this failure.

That’s the thing about this Ulwe Hill stuff. I’m hoping that this work, even in a small way, produces tension with the gallery and the art that will end up being there if or when the airport does exist.

Alana Hunt: This production of tension circles back to social, relational or community-oriented practices. A lot of my hesitancy towards those terminologies or methods is because a lot of the expectation is that you avoid tension, and make art to make some abstract notion of a “community” happy. And in doing so you seek “approval” from a community that is often outside one’s self, or perhaps that very process makes it outside. But I don’t feel art needs to be something that is necessarily approved of at all.

To imagine that you’ll reach a consensus, to secure 100% approval from any community, is absurd, because a community is an amorphous thing made of individuals, and individuals have varying opinions that also shift over time, and I feel that difference is something to treasure. I’m not saying I want disapproval. Not at all. There are many, many people that I speak to about my work, whose opinions are vital to me, but I think processes of “consultation” can be turned into a box ticking, homogenising exercise and that is dangerous. It is a process running through art, just as it runs through corporate or government approaches to development.

Art shouldn’t seek approval in a clean or neat kind of way. Art can be uncomfortable and uncertain and messy and difficult. But that said, ethics are also important. In response to the Santiago Sierra/Dark Mofo controversy Brook Andrew used the Wiradjuri word Yindyamarra, which he translated as a duty of care—something that should be systemic to life and cultural institutions but isn’t. Because of all the flawed consultation I’ve seen living here, across so many spheres, not just the arts, this word “yindyamarra” seemed to me to point to something more rigorous and complex and felt than mere consultation and approval.