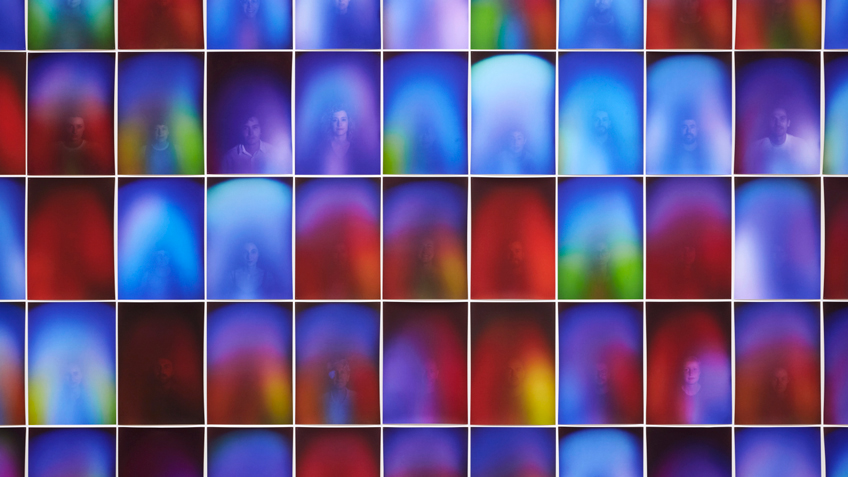

Looking up, 43 remained. Each represented by a coloured placeholder spelling the job title of an unclaimed occupation. After four months and 14,700 minutes of public interaction, Kate Mitchell had photographed 980 out of a total of 1023 occupations.

On the east wall of Bay 21 at Carriageworks was a Commissioned Fire Officer, a Concrete Pump Operator, a Gasfitter and a Hide and Skin Processing Worker, among others. To the south was a Magistrate. And to the west an Orthopaedic Surgeon, an Orthoptist, an Otorhinolaryngologist, a few more, then a Roof Plumber, a Senior Non-Commissioned Defence Force Member and a Tram Driver.

The labour of each relate to one’s or another’s body. Through medicine and manual labour, through the management of judicial and State powers, through the movement of people to places, the body is either worked on, used, controlled or transported.

In the final days of the exhibition, we were left with what the artist calls “bodily remains”.

Her labour, initially, was a means to an end. Using the Aura Camera 6000 – an ‘electromagnetic field imaging camera’ invented by American innovator Guy Coggins in the 1970s – Mitchell set herself the task of photographing the aura of one representative for each of the 1023 jobs listed on the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations. Each aura portrait captured, replaced an occupation placeholder. Gradually, pixelated placeholders – an empirical representation of working Australia – were substituted by an empathetic imagining of the workforce. Over the course of the exhibition, as each job title was swapped out, all auras (nearly) touched.

The work was repetitive and constant, starting before the exhibition opened and continuing during its run. Over four months, day in, day out, Mitchell would photograph participants, reading and interpreting their aura.

It required Mitchell to practice and preach the ‘teachings’ of this ‘technology’. In the artist’s studio, you stepped into a plastic black tent, with a peeked roof as dramatic as the spout of genie’s lamp. Seated, you placed your hands on the cold skeleton-shaped silver nodes. The Aura Camera 6000 at eye level, was an iridescent Microsoft blue. The hand plates warmed the longer your digits rested. The artist looked into the view finder, with the cable release in her hand, the shutter released, and the Polaroid was spat from the body of the camera. From the white, you emerged, steeped in inky hues. Once the colour had settled, Mitchell interpreted the immaterial.

Founded on the assertion that there is a link between our physical and our ‘energetic’ bodies, aura photography promises to conjure our consciousness. Touted as a diagnostic tool for living, New Age modalities have crept into our day to day lives. As observed by Christine Smallwood writing about astrology, we take comfort in the ‘distance’ and the ‘immediacy’ that these ‘knowledge systems’ offer. Mitchell’s use of this ‘technology’ is sympathetic to our search to explain the relationship between who we are and what we feel. Whether a sceptic or a believer, there is an undeniable magic in being able to picture yourself in colour.

At the exhibition’s end, her process had become a performance, akin to an apprenticeship. Mitchell’s art and her labour were one and the same.

The occupation list includes a Painter and a Sculptor, but no Artist. As a conceptual artist, Mitchell’s art, officially exists as unrecognised labour.

Taking the occupation data as her starting point, Mitchell draws upon the ubiquitous role of work in our life. What we do, is, for many of us, who we are. Identity and work are increasingly indistinguishable. Friederike Sigler, in her anthology Work, suggests that artistic strategies today reflect this entanglement between work and identity. She argues that our understanding of work as a subject of art is linked to how we recognise the labour that makes art, concluding that what defines contemporary practice is to “work within art and in the making of art.”

The role of work in Mitchell’s practice is both subject and process. She works herself into her art and her art into life . Known for her action-based video works, Mitchell typically assigns herself, and subsequently performs, a task. In Time (2015), she clung to the minute arm of a life-size clock for 24 hours. In the name of a Lucky Break (2013), Mitchell played her own stunt double, training and mastering the precarious art of jumping through glass. In both examples the completion of the task foregrounds Mitchell’s labour. In All Auras Touch (2020), this happened on an epic scale. Publicly, her progress towards completion was delineated by a shifting spectrum of colour. As more portraits populated the installation, the rainbow gradient was gradually broken into an irregular mosaic.

The focus on the making of art, as an artistic strategy, first surfaced in the conceptualist practices of the 1960s. In Helen Molesworth’s survey of work in art in the second half of the twentieth century, she argues that these strategies continue to be relevant today as a means of understanding how our labour shapes our identity and as a way of identifying emerging identities.

Looking back at the occupation list. To participate, fellow artists adopted literal translations of their artistic labour. One was a Linemarker. Another a Scaffolder. There was a Valuer; a Saw Doctor; and a Dog Handler or Trainer. Other participants reimagined their labour. A gamer was a Tanker Driver, adopting their online persona. A gallerist a Futures Trader. A journalist a Commodities Trader, trading in ‘ideas’ and ‘opinions’. Another, born in the Year of the Rat, and a victim of a house flood, was a Drainage, Sewage and Stormwater Labourer. Mitchell did not participate in her own work, her labour remained unaccounted for, and by implication her art invisible.

All Auras Touch conjures up the immaterial.

When the work was in development, I read an article examining consciousness. Meghan O’Gieblyn outlined how our understanding of who we are is predicated on accepting a dualism between the material and immaterial. Tracing the history of consciousness she explains, that science necessitated dismissing the mind in order to understand matter. O’Gieblyn suggests that perhaps a reason to (re)consider consciousness is that, “[c]onsciousness, after all, is the sole apparatus that connects us to the external worlds – the only way we know anything about what we have agreed to call ‘reality’.” In All Auras Touch, Mitchell asks us to imagine our existence beyond matter. Agnostic to the ‘technology’, she uses aura photography as a visual device. For the artist, colour is a means to connect what we feel to what we see; to make the invisible visible.

Colour makes feelings and it is through colour that Mitchell elicits empathy. Accepting that job titles determine how we see our self and others, the coloured portraits of each worker tested our preconceived ideas of each occupation. Awash in colour, as the artist explains, “we are all energetic beings made up of the same matter.” Mitchell’s empathic colouring allows us to consider how we are connected.

In All Auras Touch we are asked to reimagine ourselves and our relationship to one another. When reflecting on our role in the work, it is interesting to refer to Irit Rogoff’s notion of collectivity. Emphasising the plural pronoun ‘WE’, Rogoff argues that meaning is created when audiences share time and space, ‘WE’ is our collective experience and it is ‘WE’ who makes meaning. She suggests that, “what WE have is the possibility of another political space,” whereby experiencing art can be a site for action and change. In All Auras Touch, it was not the act of cataloguing each profession that was important but rather the bringing together of workers, no matter their job title. Through Mitchell’s labour almost all workers touch.

Just over a month after it has ended, our experience of the day to day has reset. Contained to our homes, our time outside is measured. Unprecedented state control determining how we use our bodies.

Our body is our focus. We’re scared and frustrated how others use and move their own.

Outside, we must measure our distance from one another, in step, our pace quickens or slows in an unconscious choreography. From windows, posted drawings beam rainbows of support for those who provide care.

Inside, comfort and company are found online. Bodiless, we must redefine how we exist together.

And our work. Lost. The confines to our bodies have limited our labour.

We wait to understand how this will continue to condition our work in time and space.

Despite our distance, what we do for ourselves we do for others.

Collective pronouns provide assurance. We are all affected.

All auras touch.

Words by Aarna Fitzgerald Hanley, Carriageworks’ Curator, Programs.

1 Christine Smallwood, “Astrology in the Age of Uncertainty”, The New Yorker, 28 October 2019.

2 Friederike Sigler, “Introduction: All That Matters Is Work,” in Work: Documents of Contemporary Art, ed. Friederike Sigler (London: Whitechapel Gallery; Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017), 16.

3 Helen Molesworth, “Work Ethic”, in Work Ethic, ed. Helen Molesworth (Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Museum of Art; University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003), 48-50.

4 Meghan O’Gieblyn, “Do We Have Minds of Our Own?”, The New Yorker, 4 December 2019.

5 Meghan O’Gieblyn, “Do We Have Minds of Our Own?” .

6 Irit Rogoff, “WE – Collectivities, Mutalities, Participations,” in I Promise It’s Political, ed. Dorothea con Hantelmann and Marjorie Jongbloed (Cologne: Museum Ludwig, 2002) 127, 128, 129-31, 133, extracted in Friederike Sigler, Work: Documents of Contemporary Art, ed. Friederike Sigler (London: Whitechapel Gallery; Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017), 117.

7 Irit Rogoff, “WE”, extracted in Sigler, Work, 119.