A sinister hum blankets a dark theatre. From the shadows, singers open their lungs and three drones begin to dance. A Drone Opera marked a new way of performing ideas of surveillance, violence and technology. Carriageworks’ Director of Programs Daniel Mudie Cunningham talks to artist Matthew Sleeth about the evolution of the work.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham: A Drone Opera has had a long and extraordinary life to date. Can you describe its back story?

Matthew Sleeth: It originally started with Claire Oliver Gallery in New York as a performative painting project. I’ve always wanted to do a machine painting project, where we would put a canvas at either end of the gallery and put paintball guns on drones. For the opening night we would do a drone painting performance and then the mess would become the exhibition – that was the original idea. We got a long way down that track and, for various reasons, mainly involving the police stopping us – it turns out to be illegal to arm drones in America (unless you’re the government of course). We then decided to make it more of a performance, which was going to be here at Carriageworks as part of ISEA 2013. That was the evolution: the gallery presentation was going to be quite brief, the presentation at Carriageworks was going to be a 15 to 20 minute painting performance and then it became a longer work and I started to think in terms of the structure and pacing of a dance piece. I’m very interested in dance and see a lot of performances – the idea of a 50-minute piece, with the ebb and flow and maybe rhythm of a dance work became the starting point for the live performances.

DMC: How did the live experience work for an audience?

MS: The live performances were commissioned by Experimenta and presented at the Meat Market in Melbourne in 2015. The show started with the audience arriving and having their phones taken and were then walked in a completely dark ante-room and held for some time before being moved, while still in darkness, into a cage like structure that was partly for protection but partly to increase anxiety. In some ways, we thought of the performances as a choreography of anxiety, a process of building and releasing anxiety. In complete darkness the audience is seated, then a large drone takes off and flies overhead, you feel the wind from it, you hear it, it ruffles your hair (if you have hair). You feel it and you hear it before you see it and then your body knows about the experience before your mind does. It was a visceral and bodily experience of something that is usually a political abstraction, something we just read or hear about.

DMC: Why the drone? To your knowledge, have drones been used in contemporary art before?

MS: It was our understanding that this was the first time they were used in a live performance with an audience indoors, which presented lots of problems, and we found out why it had not been done before. But the idea of drones came a little bit later, the original idea was to work with dancers, there was an understanding that we needed to have a human conductor for the emotion and sensory elements. I almost thought of the drones as a McGuffin, a way to talk about some of these ideas, particularly technology, surveillance and violence. But there had to be a human connection, so we started thinking about dance and did some testing with dancers until we realised they were doing something similar with their movement to the drones. The movement of the drones was choreographed and that movement aesthetic was very similar to the movement language of the dancers. The idea of opera singers came from looking for an intense sensory experience to balance the drones and lasers.

DMC: You have a very expansive practice working across multiple media. I first came to your work through photography. Interestingly, you talk about the choreography of the camera as a big part of your practice. Could you tell us a little bit about what you mean by that?

MS: My interest in drones really came from working with camera movement. A lot of my early video works involved cameras moving: on motorbikes or steadicams or cameras on people. The performance came from moving the camera, rather than the choreography of a subject in front of the camera – the camera moving was the performance. I was interested in drones as something to carry the camera originally, and also after we became aware that we were under constant surveillance. All our movements and communications were being collected, and so the idea was to use the drones as a kind of a flying panopticon that you couldn’t escape, that it would always follow you and would always see you. This was something that producer and dramaturg Kate Richards and I often talked about —how do we present these ideas and make them a visceral experience rather than just a white paper. The drone for us became a metaphor for our relationship with technology and a motif for talking about these ideas.

DMC: Three things that you talk about as being quite key for A Drone Opera are: surveillance, which you just touched on but also military violence and the fetishising of technology.

MS: The three points of the triangle were: military violence; our response to new technologies moving from fear to fetishisation and then assimilation; to the idea of surveillance—the flying panopticon. Each sequence in the opera would feature a point in the triangle that was privileged, but all three would be present, and those ideas would be explored visually and sensorially throughout the work.

DMC: In relation to this work you said to me recently that “we are worried about the wrong things”. Can you elaborate on this?

MS: I’ve been really interested for a while in this almost hysterical approach to drones from the media. I’m entertained that everyone was imagining themselves sunbaking in the nude in their backyard and a drone would fly over them – this concern was often mentioned – partly because I was impressed so many people were sunbaking nude. But, if you really want to be worried about privacy – and we should be – let’s worry about the right things. Let’s be worried about what information we give to the government, or what we give to Google or what we give to Facebook, voluntarily. This is arguably far more dangerous – and far more likely to cause problems in the future.

It’s a little bit like the fear of being in a terrorist attack, the genius of terrorism is that you fear something out of proportion to its chances of actually happening to you. Drones became a metaphor for the way that we worry about one thing, but the thing that was actually happening was doing potentially more damage, and was something that we’d taken our eyes off. So, we used drones and the ideas around surveillance to draw attention to that discussion.

DMC: The visual tropes of surveillance come through quite prominently in the work, through CIA footage.

MS: The idea of surveillance works in two ways: in the performance and in the translation of video. There was a screen that the audience could see, so the audience knew that the space they were in was being mapped, the space that was being mapped, was the space that they were in. So, they knew they could not escape which generated a kind of anxiety. The idea of surveillance for military use has really shifted from being about war to being about policing – an asymmetrical war. We are constantly told that these acts of violence are necessary for our safety and our security and our cheap oil and everything else. To make it visible, I found footage from the CIA that shows a drone tracking a person across a desert for a long time and eventually killing them. It’s quite graphic and disturbing and short fragments are woven throughout the work. We agonized about showing these images but thought it was important that we see the things that are done in our name. This thermal FLIR footage is both very graceful and very violent, paired with almost sporting commentary from the drone pilots, and makes the point viscerally rather than intellectually.

DMC: So, why opera, why not ‘A Drone Disco’? What was it about opera that attracted you?

MS: ‘A Drone Disco’ is a great idea! It was originally ‘A Drone Ballet’. That idea of dancing being equivalent to what drones do. The drones as an instrument, that, no matter what we did, there would be the drone noise. We also wanted to create a world that was weird, over-the-top and baroque, also emotional and intense, and unreasonable in a way. It was the unreasonableness and intensity of opera, that was the attraction.

DMC: Unreasonable opera?

MS: Well the distance from reality. Distance from our everyday experience.

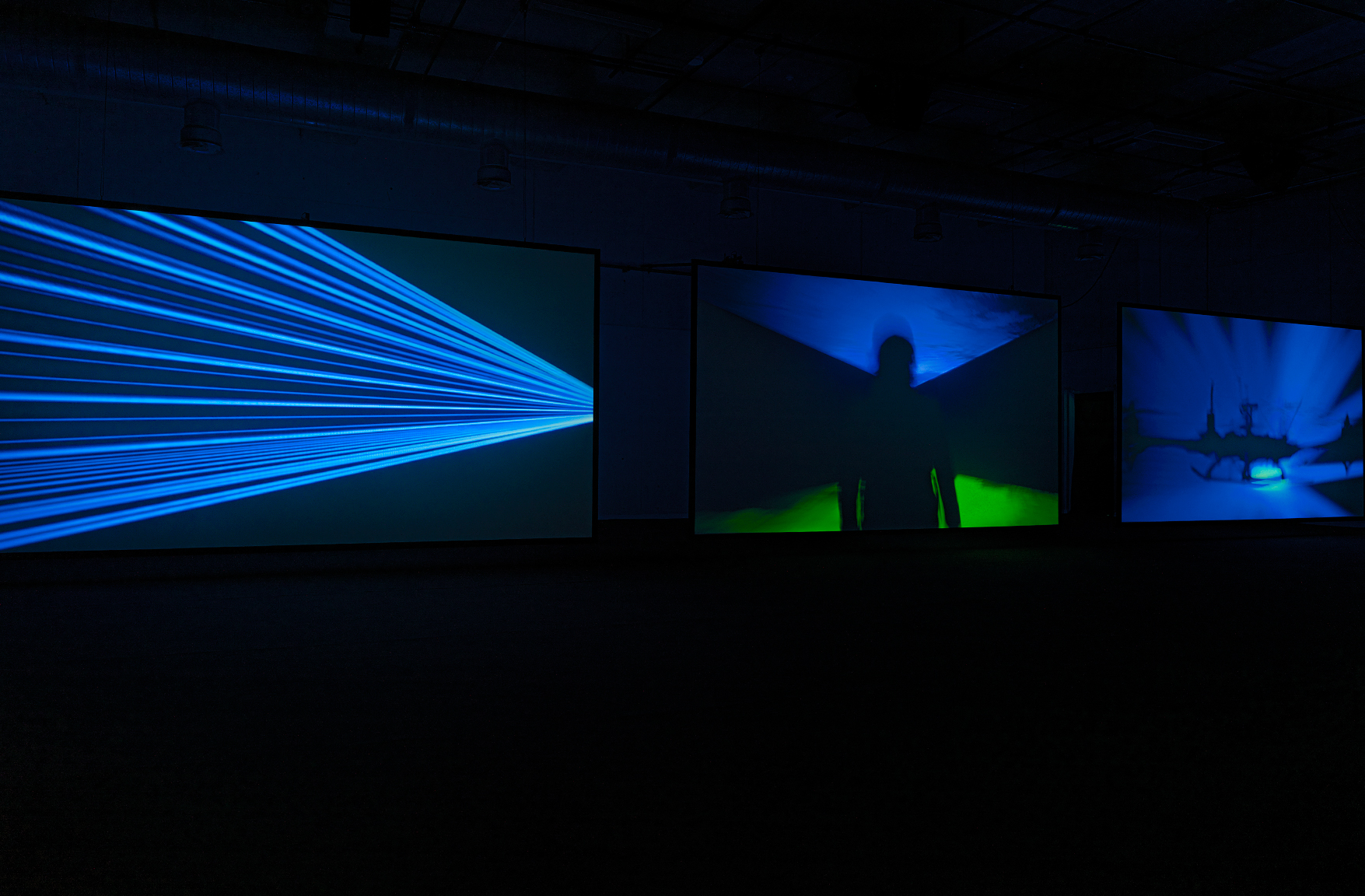

DMC: What’s so extraordinary about the work in its form as a three-channel installation is its distance, intensity and its abstraction. When inhabiting the installation, a viewer feels like you are in an ethereal, floating world, where you can’t quite ascertain what is going on. If one knows about its genesis as a live work, it is made more abstract because it has been divested of any trace of that live-ness.

MS: I generally have a disinterest in naturalism. I get enough naturalism in my daily life, I don’t want it in my art. Some footage that is present in the final edit has come from testing and development ideas that weren’t necessarily part of the performance but were part of the world we created. In the early stages of editing there were shots that contained glimpses of the audience, but we found that as soon as you saw an audience, you were watching someone else having an experience and not becoming immersed yourself, so we put a fair bit of work into removing the audience. Then you have as hermetically sealed and convincing a new world as possible.

A Drone Opera was presented at Carriageworks in June 2019. In March 2020 the work was installed at Lyon Housemuseum in Melbourne but was closed before opening to the public due to COVID-19.