Although it officially lasted just over six weeks, its consequences lingered for decades.

by Laila Ellmoos

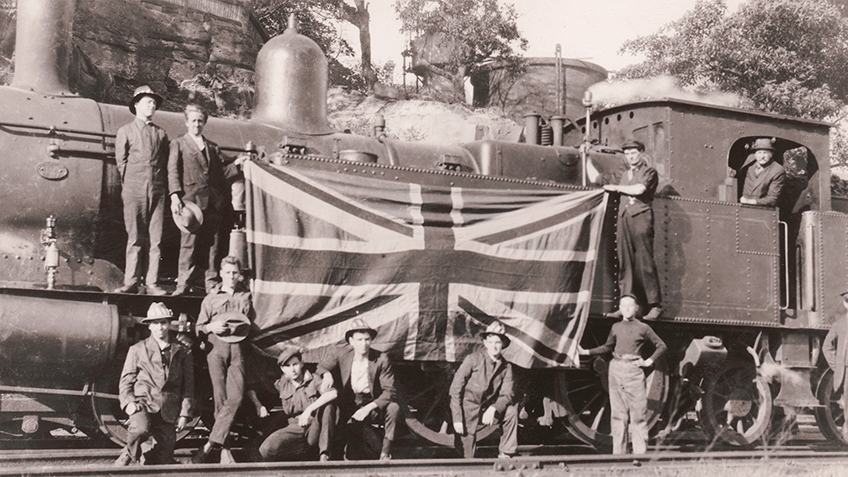

This year marks the centenary of the Great Strike of 1917, one of Australia’s largest industrial conflicts. It erupted on the NSW railways and tramways in August 1917 in response to the introduction of a new way of monitoring worker productivity.

The Eveleigh Railway Workshops, first built in the 1880s, played a significant role in the evolution of the district in the 19th and 20th centuries, not only through their physical presence, but because they provided a wide range of jobs. Employees built, repaired and maintained locomotive steam – and later diesel – engines and rolling stock; they manufactured associated metal components; and painted and upholstered train carriages. The workshops provided steady employment for local residents in the nearby suburbs of Erskineville, Macdonaldtown, Redfern, Darlington and Chippendale until the mid-20th century.

Eveleigh Railway Workshops were at the heart of political and industrial activism during the 20th century because workers had to band together to improve conditions, wages and work practices. The Great Strike of 1917 began there on 2 August when employees at Eveleigh and the Randwick Tramsheds downed tools.

Around 5790 employees at the Eveleigh and Randwick workshops walked off the job to protest against the card system that had been introduced to the railway and tramway workshops on Friday 13 July 1917. This was ‘a new system of recording work times and output’ that was intended to improve worker efficiency. Historian Lucy Taksa notes that the introduction of the card system was seen by the workers as a ‘direct attack on collective work practices and trade union principles’.

Almost two-thirds of railway and tramway employees in NSW went on strike. The strike mobilised workers across a range of industries – not just in the railways and tramways – and spread to other industrial centres throughout NSW and Australia. Overall, it is estimated that around 77,350 workers in NSW went out.

The strike spread through the imposition of ‘black bans’ and sympathy actions. Trade unions and workers withdrew their labour for the supply and distribution of primary products that had been handled by strikebreakers. This was known as a black ban. The regularity of daily life was disrupted. Because the strike had started on the railways and tramways, there was limited public transport in Sydney and NSW. Coal was declared black, which meant that many of the state’s collieries were idle, as were coal gas works across Sydney, which led to power blackouts. There were food shortages because staples, including butter and meat, were ‘black’, and because shipping was held up.

One feature of the 1917 strike was the social protest that accompanied it, which drew on strong traditions of public protest dating from the 19th century. Over the course of the industrial action, there were regular large-scale street processions and public meetings. Weekly gatherings in The Domain attracted upwards of 100,000 people, not just the striking men, but women and children too. Women were on frontline of social protest because they were working too, but also because the economic hardship caused by male workers going on strike affected whole family units.

These were heady days. World War I was in its fourth year and war-weariness was entrenched. It was a time of upheaval exacerbated by the war, new technologies and changing social values. There were government and community fears about a possible insurgency by the International Workers of the World (IWW), with the Randwick Tramsheds seen to be a particular hotbed for the ‘Wobblies’. Other world events that echoed the dissent of the times included the Irish Rebellion of 1916 and the Russian Revolutions of 1917. Locally, the conscription debates divided Australian society along class, gender and sectarian lines. Loyalties were tested.

During the strike, middle-class businessmen, farmers, university students and teenage schoolboys, called ‘scabs’ by the strike sympathisers, attempted to break the strike by doing the jobs of the striking men. The strikebreakers were housed in camps at the Sydney Cricket Ground (nicknamed the ‘Scabs Camping Ground’), Taronga Zoo and Dawes Point. The strikebreakers were called ‘volunteers’ and ‘loyalists’ by those who opposed the strike. Thousands of women also volunteered their services to help break the strike.

The strike lasted six weeks, officially ending when the Strike Defence Committee capitulated to the Railway Commissioners’ demands in mid-September 1917. But workers in maritime industries stayed out, and it wasn’t until early October that the industrial action and protest eventually wound up.

Ultimately the strike failed. In its dying days and immediately following, destitute women and children relied on relief doled out by the Women’s Relief Fund and a fund set up by the Lord Mayor. When the strike ended, many railway and tramway employees never got their jobs back. Those who were rehired found their jobs had been downgraded. The strike highlighted the split in the labour movement between ‘rank and file’ trade union members and officials. One consequence included deregistration of more than 20 unions. In the years that followed, many strikers felt they had been victimised, which in turn created working lives riven with conflict.

But the strike and its aftermath politicised a core group who were involved in it, including train driver Ben Chifley, who went on to become prime minister 1945-49. Labor stalwarts and former Eveleigh employees Joe Cahill and Eddie Ward both entered politics after their involvement in the strike. Cahill was elected NSW Premier in 1952, while Ward was a member of the House of Representatives for East Sydney 1932-60.

The nationwide strike lasted just six weeks, but its consequences endured for those involved, dividing loyalties, shaping political consciousness, and creating a highly politicised workforce and a generation of politicians, including premiers and prime ministers. Despite these legacies, this event has not been widely remembered. Its failure was considered by many to be a defeat for the labour movement, and the action was subsequently overshadowed by the memory of war and the conscription debates. This anniversary draws attention to the strike once more, allowing us to reassess this watershed moment in Australia’s history.